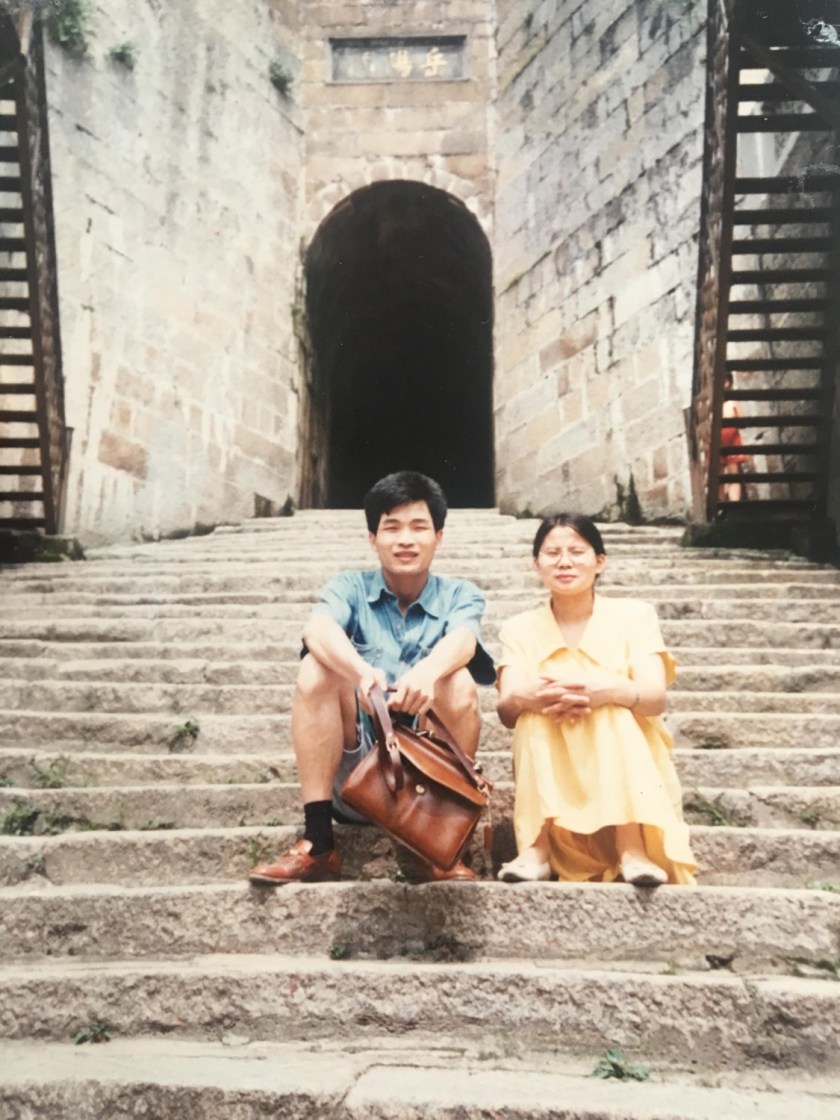

Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, 1813, Andromaque et Pyrrhus

« Andromaque, je pense à vous » c’est ainsi que Baudelaire commence à entonner sa déploration d’un Paris qui n’est plus (Le Cygne, Les Fleurs du mal, 1857). « Ce petit fleuve, Pauvre et triste miroir où jadis resplendit / L’immense majesté de vos douleurs de veuve, / Ce Simoïs menteur qui par vos pleurs grandit, / A fécondé soudain ma mémoire fertile. » Le rythme est funèbre, le ton nostalgique, le poète se place sous l’invocation de la Troyenne qui vit en une nuit disparaitre sa famille et sa cité. La veuve d’Hector, symbole séculaire de constance et de fidélité m’apparait aujourd’hui surtout comme l’archétype de la femme en exil, de celle qu’on a forcé à quitter le sol natal et qui ne trouve que dangers et périls dans un séjour étranger. Dans les textes grecs, on exalte souvent la figure de l’exilée, de celle qu’on enlève, de la captive qui suit le vainqueur sous d’autres cieux, de celle qu’un péril pousse à chercher le salut dans la fuite. Sans compagnons à leur côté, elles définissent en creux par le manque, l’absence et le chagrin.

L’idée de cette analyse m’a été soufflée lors d’une représentation récente d’Andromaquede Racine à laquelle j’ai assisté. Jamais auparavant l’acuité de la situation de cette femme éponyme ne m’avait semblé aussi flagrante. On ne parlera pas de modernité, on ne fera pas d’anachronisme, on dira simplement que rien ne change vraiment sous le soleil et que les tragiques grecs rendaient déjà compte du malheur millénaire que vivent encore aujourd’hui tant de femmes, par fait de guerre, de violence, de préjugés sociaux, étatiques ou religieux. Chacun et chacune saura entendre le lieu, le pays, où ces destins mythiques s’accomplissent encore de nos jours même si les protagonistes actuelles restent souvent sans visage et anonyme. Andromaque est avant tout une prise de guerre, elle échoit en butin à Pyrrhus, fils d’Achille qui devrait la haïr puisque la prise d’Ilion, selon la prophétie, ne pouvait s’accomplir qu’au prix du trépas de son père. Il doit la garder asservie mais voilà qu’il s’en éprend et Racine lui donne un argument déterminant pour faire sa cour, en gardant en vie Astyanax. Le jeune prince a pourtant été tué, précipité du haut des remparts de la ville par Néoptolème, si on en croit la tradition homérique et la version d’Euripide. Sur la scène classique du XVIIème siècle, il devient un enjeu de pouvoir et la victime d’un chantage amoureux.

Chez Racine, donc, Pyrrhus convoite sa prisonnière et, pour l’obliger au marriage, il fait garder son fils en otage. Qu’Andromaque l’épouse et il préservera la vie du dernier dardanien, dût-il pour cela encourir le courroux d’Oreste puis la vindicte des Grecs coalisés contre le sang d’Hector. La tragédie, composée par Racine en 1667 se résume facilement : Oreste aime Hermione, qui aime Pyrrhus, qui aime Andromaque, qui aime Hector, défunt, et qui cherche à protéger son fils Astyanax… Ce n’est plus un dilemme tragique, c’est une longue torture, un harcèlement sans fin : Accepter l’hymen honni puis se suicider semble la seule échappatoire. (Racine, Andromaque, Acte II, scène I)

PYRRHUS.

« Eh bien, madame, eh bien, il faut vous obéir :

Il faut vous oublier, ou plutôt vous haïr.

Oui, mes vœux ont trop loin poussé leur violence

Pour ne plus s’arrêter que dans l’indifférence ;

Songez-y bien : il faut désormais que mon cœur,

S’il n’aime avec transport, haïsse avec fureur.

Je n’épargnerai rien dans ma juste colère :

Le fils me répondra des mépris de la mère ;

La Grèce le demande ; et je ne prétends pas

Mettre toujours ma gloire à sauver des ingrats.

ANDROMAQUE.

Hélas, il mourra donc ! Il n’a pour sa défense

Que les pleurs de sa mère, et que son innocence…

Et peut-être après tout, en l’état où je suis,

Sa mort avancera la fin de mes ennuis.

Je prolongeais pour lui ma vie et ma misère ;

Mais enfin sur ses pas j’irai revoir son père.

Ainsi, tous trois, seigneur, par vos soins réunis,

Nous vous…

PYRRHUS.

Allez, madame, allez voir votre fils.

Peut-être, en le voyant, votre amour plus timide

Ne prendra pas toujours sa colère pour guide.

Pour savoir nos destins j’irai vous retrouver :

Madame, en l’embrassant, songez à le sauver. »

Andromaque, HécubeetLes Troyennesd’Euripide, composées respectivement en 424 et en 415, donnaient déjà le ton : la princesse Polyxène fut immolée sur le tombeau d’Achille, Cassandre, fille de Priam et désirée par Apollon, fut violée par Ajax, fils d’Oïlée, après avoir été arrachée à la protection du Palladium, contrainte ensuite à suivre Agamemnon, tuée enfin sur ordre de Clytemnestre (Homère, Odyssée, Chant XI). Eschyle avait décrit Cassandre affolée par ses pouvoirs divinatoires, Euripide la montrait tremblante et comme anéantie devant l’épouvantable engrenage qui la conduisait à la mort. Sénèque lui faisait décrire l’horreur de la chute de Troie, le carnage qui suivit et les maux sans fin qu’elle souffrait deux fois puisqu’elle les anticipait sans pouvoir les éviter.

Dans l’incipit des Troyennes, Neptune s’apprête donc à quitter la ville de Priam qu’il protégea longtemps, il introduit l’action avant de s’adresser à Athéna, protectrice des Achéens victorieux :

« Le Scamandre retentit des lamentations des captives à qui le sort vient d’assigner un maître. Les unes sont échues aux Arcadiens, les autres aux Thessaliens, d’autres aux fils de Thésée, rois d’Athènes. Celles des Troyennes qui n’ont pas été tirées au sort sont dans cette tente, réservées aux chefs de l’armée ; la fille de Tyndare, Hélène, est avec elles, et c’est avec justice qu’on la compte parmi les captives. Là, s’offre à tous les regards l’infortunée Hécube ; prosternée à l’entrée de la tente, elle verse des larmes abondantes sur la perte de tout ce qui lui fut cher. Sa fille Polyxène vient d’être immolée sur le tombeau d’Achille, à l’insu de sa mère ; Priam n’est plus, ses enfants ne sont plus; et celle dont Apollon respecta la virginité, Cassandre, qu’inspire l’esprit prophétique, Agamemnon, au mépris du dieu et par une violence impie, la contraint de s’unir à lui par une alliance clandestine. »

La tragédie desTroyennes s’insère dans une trilogie, la pièce s’ouvre sur un rappel de la prise d’Ilion avant que chaque captive soit fixée sur son sort. Chacune devra en effet suivre un maître. Cassandre accompagnera Agamemnon à Mycènes, Andromaque sera remise à Néoptolème et la reine Hécube donnée à Ulysse, son plus farouche ennemi. Comme les servantes à Ithaque, pendues sur ordre d’Ulysse, les Troyennes n’ont aucune défense, aucun droit. Vae Victis. Leurs chants se succèdent, égrenant le destin croisé de ces femmes contraintes à l’exil, soumises aux volontés des vainqueurs.

Hécube ira encore en Thrace venger son dernier fils que Priam croyait avoir confié à la protection d’un roi ami. Le traitre Polymnestor, fourbe et cupide, tua l’enfant pour conserver les trésors qu’on lui avait remis avec sa garde. Entre les deux premiers épisodes des Troyennesqui scellent le sort de Cassandre avec celui d’Andromaque et les adieux finals d’Hécube, une longue joute oppose également Ménélas à Hélène, la belle Hélène, le casus belliféminin du conflit, que son époux entend mettre à mort dès qu’ils auront regagné Sparte. Victime, elle l’est aussi, si on se souvient du rapt qui la conduisit avec Pâris en Troade, jouet à la fois de la Discorde en colère et du jugement de trois déesses vaniteuses. Dans La guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu,en 1935, Giraudoux campe une Hélène languide et changeante, aguicheuse mais sans volonté claire, tour à tour artificieuse et naïve, une femme dont l’essencese résume à sa seule beauté et dont l’existencedépend du regard et des exigences des hommes.

S’il demeure un sentiment de tragique devant la fatalité qui s’acharne sur les personnages féminins des Troyennes, on se rend vite compte que la guerre reste avant tout une chose sordide et vile. Dégrisés après la fureur des batailles, les héros masculins font pour une fois piètres figures. Les plaintes pathétiques des trois femmes et de celles qui composent le chœur, en écho, suscitent la pitié et la compassion. Il ne reste plus rien de grand ni de courageux à accomplir sur les décombres de Troie. Ni la piété due aux Dieux, ni le respect pour l’âge et pour la majesté déchue n’ont droit de cité Les Troyennes n’ont survécu que pour devenir proie, elles ont porté le deuil de leurs pères, de leurs frères, de leurs époux, de leurs fils avant de devenir les esclaves des Achéens. Il ne demeure vraiment rien de glorieux dans la pièce d’Euripide mais la catharsisaristotélicienne fonctionne parfaitement : la terreur et la pitié saisissent le lecteur, foudroient le spectateur. Il faut donc partir, sans rien, sans autre bagage que des souvenirs, avec l’icône d’un époux adoré comme Andromaque ou avec les cendres d’un fils comme Hécube qui devient la sépulture vivante de son fils Hector.

D’autres femmes fuient encore et toujours. Les filles de Danaos refusent un mariage imposé avec leurs cousins et cherchent refuge en Grèce. Les Suppliantesd’Eschyle, vers 466, nous les montrent éperdues arrivant en Argos, ne pouvant se résoudre à épouser leurs prétendants imposés. Poursuivies par leurs fiancés, les fils d’Egyptos, elles chantent la douleur de quitter le sol de Lybie, d’être démunies et sans soutien aucun en pays étranger. Le roi Pelasge les accueille avec bienveillance. Il entend même leur supplique mais la guerre gronde aux frontières alors que se referme le premier volet de la trilogie dont ils nous manquent les deux suivants. La menace imminente rend leur asile fragile, leur situation précaire. La suite des pérégrinations des Danaïdes est connue : Contraintes aux noces, elles accompliront dans la nuit qui les suivra le meurtre de leurs époux et seront condamnée pour l’éternité à remplir d’eau un récipient sans fond.

Revenons à Troie, avec une pointe d’humour… Le seul être qui, finalement, comprendra Andromaque, se nomme Léopold, (Marcel, Aymé, Uranus1948), Léopold le simplet, Léopold le cabaretier, un grand ami de la dive bouteille, qui s’éprend d’Andromaque rien qu’en écoutant l’instituteur faire cours sur Racine, dans son café, car l’école a été détruite par les bombardements de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. Parmi les décombres d’une sempiternelle guerre, le cafetier ému improvise des alexandrins en comptant les pieds sur ses doigts, des vers boiteux mais si émouvants, pour sauver la veuve d’Hector et le rejeton d’Ilion. Léopold est incapable de la laisser subir un sort qu’il juge épouvantable. Andromaque s’extasie, fort prosaïquement mais visiblement soulagée d’avoir trouvé enfin un allié.

LEOPOLD :

« Passez-moi Astyanax, on va filer en douce – Attendons pas d’avoir les poulets à nos trousses.

ANDROMAQUE :

Mon Dieu, c’est-il possible. Enfin voilà un homme ! Voulez-vous du vin blanc ou voulez-vous du rhum ?

LEOPOLD:

Du blanc !

ANDROMAQUE:

C’est du blanc que buvait mon Hector pour monter au front.

Il n’avait pas tort.

The Dinner Party est une installation artistique de Judy Chicago qu’on peut voir dans l’aile appelée Elizabeth A. Sackler center for Feminist Art du Brooklyn Museum de New York. La structure en forme de table de banquet triangulaire fut élaborée de façon collective entre 1974 et 1979. Cette œuvre a été autant décriée qu’encensée mais elle possède l’immense mérite de proposer une lecture épique des destins de centaines de figures féminines historiques ou mythiques. Elles sont au nombre de 1038, référencées directement ou symboliquement. Hélène et Hécube y figurent. Juste revanche ? On pourrait légitimement ajouter Andromaque, si affligée, si forte aussi.

Sophie Rochefort-Guillouet is a history professor at Sciences Po Paris Campus du Havre.