By Gemma Tabet

Today, the Sama Dilaut or Sea Nomads, remain one of the world’s last ethnic communities living solely on water. For centuries they have made their livelihood amongst the seas of Maritime Southeast Asia, travelling between the coasts and islands of Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines (Lenhart, 1995). They rely on sea-based activities, such as fishing and trade, and live on their boats (called lepa) or on stilt houses above water (Borneo History, 2017). The Sama Dilaut even developed unique skills that allowed them over the centuries to live in harmony with their aquatic environment. For example, they developed physical advantages such as a 50% increase in spleen size, allowing them to stay underwater for 10 minutes at a time at depths of 70 metres (Sieber, 2023). But modern times have brought harsh challenges, from over-tourism to climate change, that threaten the Sama Dilaut’s centuries-old way of life.

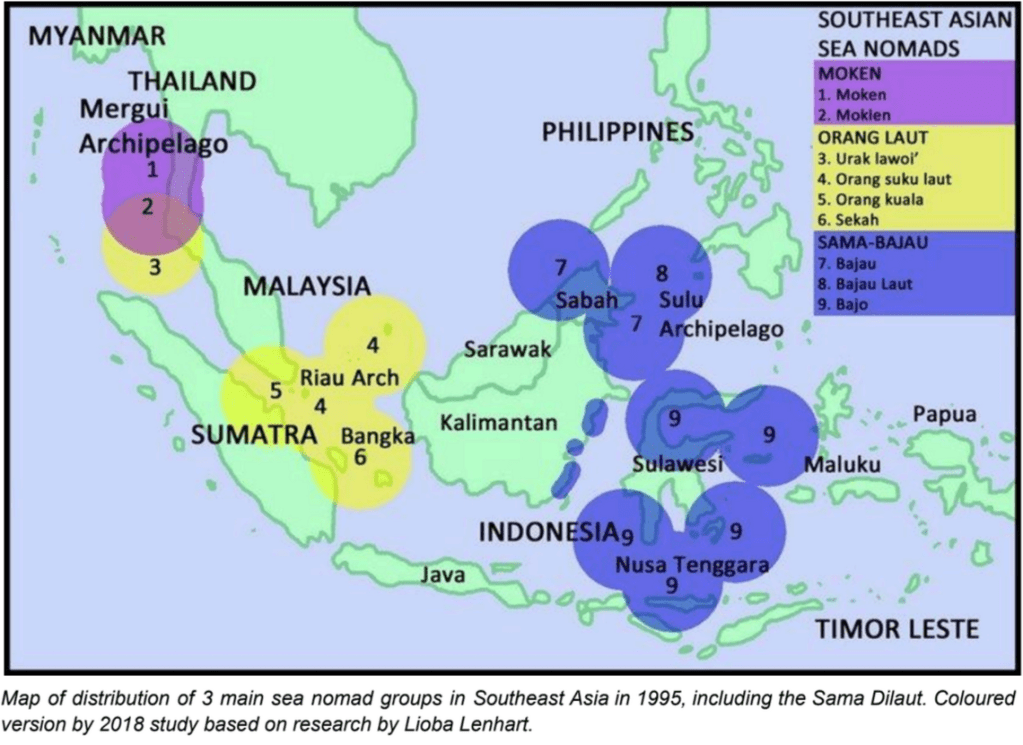

The Sama Dilaut peoples are part of a larger ethnolinguistic group known as Sama, which consists of two other categories: the land-based Sama Dileya/Dea and coastal Sama Lipid/Bihing (Maglana, 2016). Commonly, these populations fall under the category “Sama-Bajau”, but many groups self-designate themselves using toponyms based on place of origin (Maglana, 2016), such as Sama Sitangkai (Sama of Sitangkai Island). Further distinguishing this community is the presence of 10 major languages and a variety of religious systems (Maglana, 2016). The Sama Dilaut, unlike their land-based counterparts, are less influenced by Islam (the main religion in the region today), due to the remaining impacts of ancestral beliefs based on animism (Saat, 2003). The exact land origins of the Sama Dilaut remain still unclear, but first references can be traced back to 840 CE in the Darangen (Borneo History, 2017), an epic oral poem by the Maranao (an Islamic cultural-linguistic group in the Philippines), which mentions a love story between a Sama Dilaut princess and Maranao prince. Since then, the Sama Dilaut have settled in the waters surrounding Sabah, the Sulu Archipelago, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Nusa Tengarra (Lenhart, 1995), leading to a unique cultural identity tied to the seas.

Yet today, this historic culture and community face modern challenges linked to political marginalisation, discrimination (Moreno, 2023), and environmental degradation (Musawah, 2024), that threaten to erase centuries of traditional knowledge and practices.

The marginalisation of the Sama Dilaut can be traced back to European colonial rule, which led to the establishment of maritime borders that disrupted the Sama Dilaut´s way of life (Sieber, 2023). For example, trade networks for the procurement and exportation of turtle shells, sea cucumbers, and general fishing existing since 1000 BCE (Jeon, 2019) were no longer viable, greatly affecting one of the main sources of income for the community. The Sama Dilaut have only further lost access to their traditional fishing sites, exacerbating their economic vulnerability and contributing to rising levels of poverty (Moreno, 2023). Particularly, the modern ´stateless status´ of the Sama Dilaut has increased levels of alienation and marginalisation by limiting their legal privileges (Moreno, 2023). Due to unclear legislation distinguishing asylum seekers, irregular migrants, and undocumented or stateless individuals, Sama Dilaut are not often granted citizenship (Sieber, 2023). For example, in the Philippines the Indigenous People´s Act (Act No. 8371) covers only peoples from ancestral lands and not oceanic waters. This reflects the wider political realities the community is subjected to, leading to direct lack of access to essential services, such as education, formal employment, and healthcare (Sieber, 2023).

Beyond a lack of legal recognition and policies for ensuring the economic and political protection of this vulnerable ethnic minority, the Sama Dilaut face centuries old discrimination that has eroded their culture and traditional knowledge (Moreno, 2023). The Sama Dilaut in the Sulu Archipelago are still today victims of historic cultural prejudice (Saat, 2023) originating from dominant land-based groups (like the Tausūg, a Muslim ethnic group in the Philippines and Malaysia). These groups viewed boat dwelling and un-Islamic animism practices as inferior and uncivilised, earning the Sama Dilaut a low social status (Saat, 2003). For example, the Tausūg people have a derogatory name for the Sama Dilaut that translates to “spat out” (Nimmo, 1968). This history of discrimination still ripples into the modern world, leading to the cultural assimilation of the Sama Dilaut, who more and more migrate to land, abandoning their sea-faring way of life (Sieber, 2023). A rising number of Sama Dilaut have converted to Islam over the years (Maglana, 2016), a key example of cultural conformation due to social pressure. The preservation of the Sama Dilaut´s unique customs has severely declined, impacting their traditional languages, religions, and practises.

Moreover, the nomadic ways of the Sama Dilaut have further been challenged by overfishing and climate change (Musawah, 2024). Due to their economic difficulties, many Sama Dilaut have small and underdeveloped boats and fishing tools (Jeon, 2019, pg. 50), already placing them at a disadvantage when competing with modern fishing corporations. Climate change has only exacerbated the situation, leading to ocean acidification that causes fish migration, forcing various Sama Dilaut to settle on land as they lose access to their primary source of livelihood (Musawah, 2024). There, they may turn to seaweed farming, but because of exploitation by intermediaries, the Sama Dilaut fail to earn enough income (Musawah, 2024). In their struggle against poverty, some Sama Dilaut introduce chemicals and fertilisers into their farming, harming sea life and their own connection to the ocean (Musawah, 2024). The Sama Dilaut are placed further at risk due to extreme weather changes caused by global warming, such as rising sea levels and typhoons (Moreno, 2023).

In conclusion, it is evident that the Sama Dilaut face a variety of challenges that threaten to erode and erase their nomadic cultures and lives. From political marginalisation and discrimination rooted in the past, to modern perils caused by climate change, the Sama Dilaut are socially, politically, and economically vulnerable. These indigenous peoples have centuries old knowledge of currents, marine ecosystems, star charts, and wind patterns (Maglana, 2016, pg. 78) that could be critically important for better understanding the impacts of and solutions to climate change. A variety of organisations have worked over the years to ensure the political and socio-economic protection of the Sama Dilaut. For example, Rosalyn Diwala´s Indigenous Children’s Learning Centers aim to organise education courses led by native teachers for Sama Dilaut children. On a larger scale, in February 2024, during the World Conference on Statelessness, an understanding was made between the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia to address the Sama Dilaut situation. More concentrated efforts and policies to deal with the specific plights faced by this community are needed urgently, in order to ensure the preservation of not only a unique culture, but to also ensure the protection of a critically vulnerable ethnic community.

Disclaimer: As a student, I don’t have the full capacity nor time to delve into the complexities of each ethnic community. My intention is to create a space dedicated to introducing readers to different minorities and their plights, to raise awareness and to encourage further readings into such topics.