by Lino Battin

“I don’t know that anyone who has seen the images would not have strong feelings about what has happened, much less those who have relatives who have died and been killed, and I know people and have talked with people. So, I appreciate that, but I also do know that for many people who care about this issue, they also care about bringing down the price of groceries.” – Kamala Harris

When 235 years ago the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was proclaimed, it brought with it a promise of egalitarianism and universalism, “men are born and remain equal and free in rights”. To anyone even slightly interested in our history this should raise a big question. How could it be possible, that while professing its love for “liberté, égalité, fraternité,” France and its fellow European imperial powers enslaved, massacred, and exterminated the better part of our planet? Of course, it does not help that its authors were all fervent racists who thought of dark skin as a subhuman trait, but let us take a broader look at the historical context surrounding the advent of colonialism, transatlantic slavery, and racism.

Racism as a posteriori justification for economic submission

No matter how much one pretends to look beyond complexion, or to “not see colour”, race still plays an inevitable role all around the world, seeping into all aspects of social life. Despite this, we rarely take a step back to consider the category of race, what it means and how it came to be.

Firstly, it is necessary to understand the basic notion that race is a social construct, fabricated by a specific group of human beings. This is not a value judgement, after all there exists a number of very valuable social constructs, rather it refutes the idea of race being something biological and immutable.

In this video, which I strongly recommend, the history of the invention of race and racism is laid out. Before the invention of racism, say somewhere in the 1500s, a European person would identify along religious, national, or regional lines, no one would have thought of themselves as white or any other racial term. The first racism, or proto racism came from the Muslim world, which through its sub-Saharan expansions encountered what we today call black people. At this point, slavery was not a new practice and had persisted for countless centuries, it was however predicated along religious lines, meaning that Muslims could only enslave non-Muslim people, Christians could only enslave non-Christian people, and so on. The north African Muslims thus took large amounts of non-Muslim black slaves, which they then exported throughout the Muslim world, from the Iberian Peninsula to the border of China. These sub-Saharan slaves were considered inferior even to other slaves, seen as a distinct group and worth less. It is of great importance to note that contrary to European, Christian racism, this was very much a niche perspective and not socially accepted. Muslim scholars and jurors throughout the Muslim world argued for the equality of all Muslims regardless of skin colour, and never were any race-specific laws passed.

Things happened differently in Europe. In the Iberian Peninsula, in areas free of Muslim rule, the Christian kings passed “blood purity laws”, targeting the Jewish and Muslim populations, discriminating against them legally, barring them from essentially every part of society. Once the Reconquista was completed and Christians ruled over the entire peninsula, the blood laws were also expanded across the entire region. The Iberian Muslims now living under Christian rule, along with the Iberian Jews were now facing systematic discrimination and were suspected, even after conversion, of trying to betray and destroy their Christian rulers. These laws also applied to converts’ descendants, setting an important precedent of hereditary oppression. These laws, horrible as they were, still were not racist and targeted religious identities. This would change with the colonisation of the Americas, and the subsequent imports of African slaves into the colonies.

The Spaniards started enslaving people as soon as they set foot on American soil. As mentioned before, according to Spanish law, only non-Christians could be enslaved, and according to Spanish jurisprudence, indigenous American people could not simply be enslaved as they had never come into contact with Christ and his people. Therefore, at least officially, the Europeans were obliged to give the indigenous people a chance to convert to Christianity. In practice however, this was not really applied: an example of a loophole to this doctrine was the reading of a Spanish document, detailing the necessary steps to conversion, to a group of Amerindians, who of course did not understand Spanish. This was then considered good enough to enslave them, but still not on racial grounds, rather on national and religious ones. When Spain started importing African Slaves into the American colonies, those “progressive” Spaniards calling for improved indigenous rights, had none of that compassion for the slaves. Yet there still was no legal basis for their enslavement, and as Spanish reformer Bartolomé de las Casas pointed out, Africans in the Americas were enslaved illegally. This was a problem for Spanish authorities, as they required the labour of the slaves in the colonies, and so they found refuge in the bible. Indeed, to justify the enslavement of black people regardless of their religion, the Curse of Ham was invoked. According to some Christian, Jewish, and Muslim interpretations, Ham was the father of the Africans. In the Old Testament, Noah cursed Ham’s descendants to be slaves, which were considered by the Spaniards to be all Africans. Consequently, the very powerful Spanish catholic authorities in the Americas successfully pressured the Suprema (the council of Spanish catholic kingdoms) to include the category of blackness in the blood-purity laws, thus making black people legally discriminated against because of their physical appearance rather than because of their religion.

Now that blackness was well defined in law, it spread to other colonies, essentially becoming the legal norm in Europe. Whiteness, however, was yet to be defined – that task was to be left to the British.

In the late 16th to early 17th centuries, when the United Kingdom started colonising the Americas and importing African slaves, it lacked a powerful religious institution like the Spanish church or the equivalent of “blood purity laws”, leaving individual colonies to make their own laws concerning race and slavery. Barbados for example drafted laws legalising the lifelong enslavement of “negroes and Indians”, further cementing slave-ness as a “non-European” trait. In the British Caribbean colonies, there were both slaves and indentured servants, of whom most were Europeans, who either concluded voluntary contracts, or were sent to the colonies as punishment (there were for example considerable amounts of Irish rebels). While both were treated brutally, the servants’ oppression was bound by a contract which came to an end, their children would not be born indentured labourers, and they enjoyed rights and protections which the slaves did not. Despite this difference in status, the two groups realised they had common interests in fighting the British ruling class, and thus on many occasions combined forces to fight the British together. This of course greatly worried the British, who saw the united front of European indentured servants and African slaves as a genuine threat to their fabricated racial hierarchy, and to their colonial system more broadly.

To avoid cooperation between the two, colonial authorities introduced a law in Barbados in 1661 dividing labouring classes into Christians and Negroes, rather than indentured servants and slaves. Indentured servants saw their conditions improve massively, from hugely reduced punishments for disobedience, enormous increases in fines for killing servants, to rewarding servants with their freedom should they manage to catch a runaway slave. In short, the servants were integrated into an in group, while the slaves were clearly defined as the out group. This drove an enormous wedge in between the two groups. Following the introduction of this law in Barbados, other colonies such as Jamaica followed suit. The rising popularity of such laws posed a legal issue to the United Kingdom, as jurisprudence stated that baptism would enfranchise a slave, and that slavery was thus dependent on non-Christian status. To resolve this issue, more laws were passed, such as the 1681 Servant Act. This legislation replaced “Christian”, with “White” and thereby, for the first time in history, created the dichotomy between black or negro slaves, and white free men. Following this law, black slaves were denied suing for freedom on a religious basis and many colonies quickly followed suit in implementing such laws. The notion of racial whiteness spread across the Americas and shaped social relations as we know them today. For much more information and further reading I again recommend this video.

The status quo today

A few things have of course changed since the epoch of the Spanish inquisition and transatlantic slave trade. No longer is the world directly administered by a handful of European nations, yet the unequal relationship between the formerly colonising powers, i.e. the first world, and the formerly colonised countries i.e. the third world, is anything but a thing of the past. While the sun now indeed sets on the British empire, international inequalities have persisted and even worsened in recent decades. While neoliberal ideologues will claim this to be a bug rather than a feature of capitalism, I argue this to be false, and global inequality to be very much an intentional and necessary part of the capitalist system. There have been many theories of the unequal relationship between countries, from Lenin’s theory of imperialism to dependency theory and the theory of unequal exchange.

In this article I will be focussing principally on the theory of unequal exchange as formulated by Arghiri Emmanuel, since it addresses most aptly our current state of affairs in my opinion. While it would go beyond the scope of this text to explain in depth Emmanuel’s theories, I will provide a simplification. His basic idea is that one hour of labour in an underdeveloped nation is exchanged for less than an hour of labour in a developed nation, in other words, labour is being drained from the underdeveloped to the developed world. Due to neoliberal policies, capital is highly mobile around the world, whereas labour is relatively immobile, workers cannot simply move around to find wherever suits them best. Because of capital’s relatively high mobility, it will flow to places with higher rates of profit, until profit rates equalise in the competitive market. Wages however will not equalise, due to labour’s relative immobility. The cost of labour (or wages) is systematically lower in the third world, due to the structural adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund, or comprador regimes, crushing labour movements in service of their first world handlers. The third-world’s workers’ time is thus valued lower than that of the first world worker, whose wage is secure thanks to solid trade union structures and state support, making them almost a separate class, a “labour aristocracy” as Lenin would have said. If you are interested in the mathematics and the modelling of this theory, I recommend this video as a nice introduction.

I focus on this theory in particular because, in the last few years, very interesting empirical research has been conducted on the subject of value transfers, made possible thanks to large trade-databases and new digital tools. These studies’ findings are quite incredible – I will present them here. In 2018, Andrea Ricci found that value transfers from underdeveloped to developed countries rose from $704 billion (or 3.1% of world GDP) in 1990, to $3,924 billion (or 4.5% of world GDP) in 2019. In contrast, the respective amounts of total development assistance for those respective years were $59.3 billion and $165.8 billion (2018). During the 2010s, these value transfers contributed around 8% of GDP in first-world countries, while costing “value-donors”, namely south-east Asian and African countries, as much as 20% of their GDP. Another recent study focused on measuring flows of labour in the world economy. It finds that in 2021 alone, the global north appropriated 826 billion hours of labour, corresponding to €16.9 trillion in northern prices. Furthermore, it puts numbers on the labour relations between the global north and south: for work of equal skill, southern wages are 87-95% lower than in the north, meaning a software engineer based in India will make around 90% less than his German or American counterpart, doing the same work, sometimes even for the same company. Finally, while global south workers contribute 90% of the world’s labour, they receive only 21% of global income.

I bring up these facts because they are crucial to understanding how unsustainable and impossible to universalise our development model is, as it necessitates the appropriation of labour from the vast majority of humanity.

The continuing dehumanisation of the third world

We have now established that our current way of living is and has been for the last centuries, based on the appropriation of unimaginable amounts of wealth from the third world, or the global south. The hierarchisation of humanity into lower races was a necessary part of justifying this merciless bondage for economic extraction by the white race. Now we can look at how this phenomenon persists.

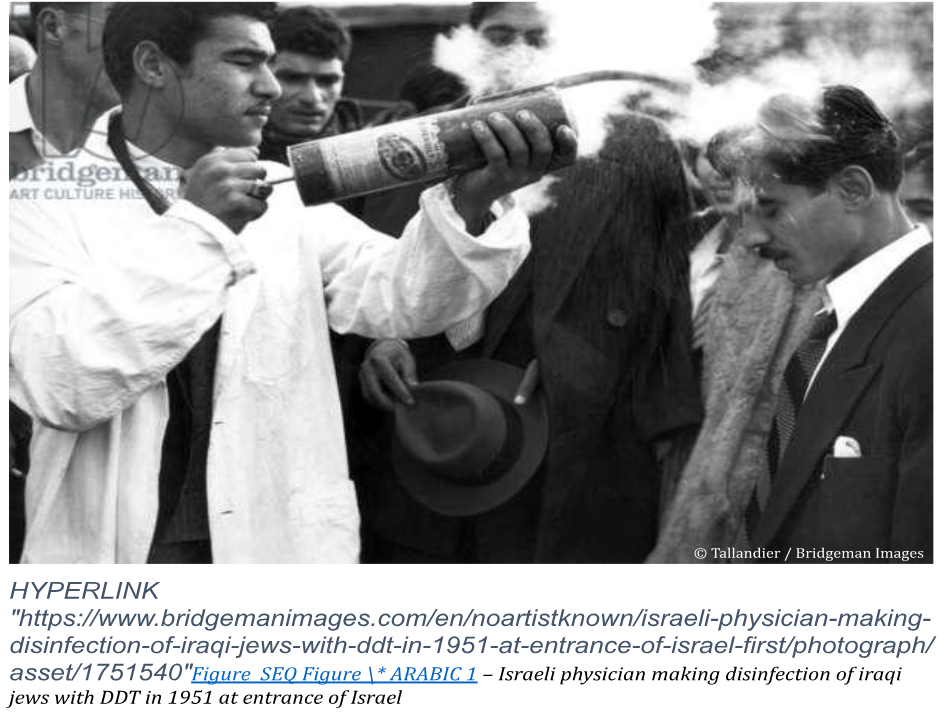

A racialised person today is no longer bound to be enslaved due to their phenotype, or due to their ancestors being slaves. Racism, however, is as alive today as it was over the last centuries, sometimes more subtly, but nevertheless carrying with itself its characteristic brutality. The “civilised world” enables and funds campaigns of ethnic cleansing and extermination in Palestine, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, West Papua, and more. Not only that, but even inside of the core these scourges persist. In my native Austria, 76 percent of black people face racial discrimination, and indeed racist abuse is increasing across the European Union. It is important to recognise that these two facts are connected, this hatred is after all manufactured by the same actors committing and or benefitting from the aforementioned atrocities. Racism is not persistent in our societies because of some immutable trait of ours, but because it is taught anew to every generation, by those who sit on top of the social hierarchy: the owners of newspapers, TV-channels, politicians, religious leaders, etc. To quote from anthropologist Carole Nagengast: “This justifies first symbolic and then too often physical violence against [subordinates]. And that requires the implicit agreement and cooperation of ordinary nice people who have been inoculated with evil, who learn to take myths at face value, and who do not question the projects of the state in defence of a social order that requires hierarchy. Only when general consensus has been created can ordinary people (read the dominant group) actively participate in human rights abuses, explicitly support them, or turn their faces and pretend not to know even when confronted with incontrovertible evidence of them.”

Besides this system of indoctrination, there is the unfortunate fact that first world citizens, be they capitalists or not, benefit from the plunder of the global South. The much-famed Scandinavian welfare states, the British National Health Service, or Switzerland’s lauded public infrastructure would never have been possible without this unequal exchange between north and south. We must ask the unfortunate question of whether the radical change necessary to stop unequal exchange can come from the first world, or if the convenience of cheap goods as put forward by Kamala Harris, and relative safety and stability is enough to appease the people of the first world and let them watch as the majority of humanity is underdeveloped, pillaged, and killed.

Conclusion

The gist of this article is thus: regardless of political orientation (albeit with very few exceptions), relevant first world political forces still do not consider third world people worthy of consideration. Rather they are seen as things to be pitied at best, an unfortunate but inevitable fact of life and a wild “jungle” to be controlled, as the EU’s top diplomat Josep Borell puts it. They are hardly recognised as individuals, but are rather seen as faceless and mindless collectives, somehow intrinsically different to us. This is not because of evil individual leaders or populism, but because it is necessary for us to dehumanise those we destroy and exploit. The unfortunate truth is that it would hurt the bottom line of pretty much every big company if first world consumers felt genuine empathy at the plight of the majority of humanity. Therefore, capital does all it can, through politics, art, religion, etc. to keep us indifferent at best and hateful at worst. Its success is palpable and is exemplified by how mainstream forms of racism such as islamophobia are.

We must centre the third world in our analysis and consider the world from its perspective; it does after all represent the vast majority of us humans. We must reckon with such uncomfortable questions as whether international class solidarity can exist as long as some peoples benefit from the exploitation of others. And, most importantly, we, the first world, must realise that we are not the priority in world affairs.