Romantisme rime avec rupture. Charles Maurras va jusqu’à inclure ce mouvement dans sa trilogie honnie : Réforme, Révolution, Romantisme pour stigmatiser la décadence française qui, à ses yeux, suivit l’apogée du classicisme, avec le déclin du catholicisme et la fin de l’absolutisme capétien. Ce courant marche de fait au pas du Siècle des Révolutions, démocratiques et nationales, il les accompagne, exalte la liberté de l’individu, le lyrisme de la communauté historique, le choix du spirituel face au la spirituel face au matérialisme des Lumières. Le cœur contre la raison ? Ce serait trop simple. Les artistes romantiques affirment certains primats : celui des sentiments, de la nature, du mystère, du désir d’infini, du spleen sur l’ordonnancement d’un monde balisé et domestiqué. Peintres, poètes ou bien musiciens, ils sont de grands voyageurs, visiteurs d’un Orient fantasmé, de contrées septentrionales, de régions méridiennes, navigateurs sur fond de rêves ou de cauchemars infinis. La nuit, la folie, la violence et la mort les aimantent. Ils vivent l’amour comme on subit une malédiction, la foi comme on affronte un châtiment. Connaissant le monde, ils s’en détournent avec un certain dédain pour chercher une réalité sublimée, un ailleurs, une contrée solitaire dont leur âme sait les chemins. Ils meurent souvent jeunes, comme si cette Icarie réclamait pour y accéder le sésame d’une vie aussi incandescente que brève.

Les peintres de la génération romantique rompent avec les sujets académiques ou, s’ils y consentent, les métamorphosent et les plient à leur inspiration. L’Histoire revisitée devient épique voire vénéneuse chez Delacroix, dantesque et cruelle chez Goya. Elle est dramatisée et prend des allures universelles lorsque le peintre espagnol transcrit les horreurs de la guerre et les souffrances des hommes. Un colosse, géant cerné de brouillard peint par Goya entre 1808 et 1810, suscite une terreur intense chez des hommes à taille de fourmis. L’imaginaire goyesque dépasse ici de loin la simple dénonciation d’une brutale campagne militaire. Cette panique renvoie aux racines antiques, renoue avec la peur primale. Chez Delacroix, Sardanapale, indifférent, repose sur des cousins en contemplant le chaos et ce carnage qu’il a ordonné. La violence sourd de cette œuvre peinte par Delacroix en 1827. Le peintre de la Liberté guidant le peuple interroge l’Histoire, celle de la Grèce luttant pour son indépendance, celle de Rome croulant sous sa propre grandeur. Il s’en dégage un pessimisme profond quant au progrès dont serait capable le genre humain. Delacroix consigne tour à tour les avancées et les reculs de l’humanité, sollicite Scott et Shakespeare, tend vers le mythe et va jusqu’à en créer certains, telle cette Marianne sur une barricade. Comme Chassériau, il rentre d’Orient ébloui par l’indolence des femmes et le contraste entre ombre et lumière. Comme Géricault, il saisit la tension et l’énergie brutes, les résume dans ces chevaux frémissants, cavales des fantasias marocaines ou encore étalon de Mazeppa. Derrière l’œuvre picturale romantique se lit en filigrane un message qui dépasse le pittoresque ou l’anecdote. « C’est la grande armée, c’est le soldat, ou plutôt c’est l’homme ; c’est la misère humaine toute seule, sous un ciel brumeux, sur un sol de glace, sans guide, sans chef, sans distinction. C’est le désespoir dans le désert. » Ainsi s’exprime Alfred de Musset, au sujet d’Épisode de la campagne de Russie de Charlet, une œuvre présentée au Salon de 1836.

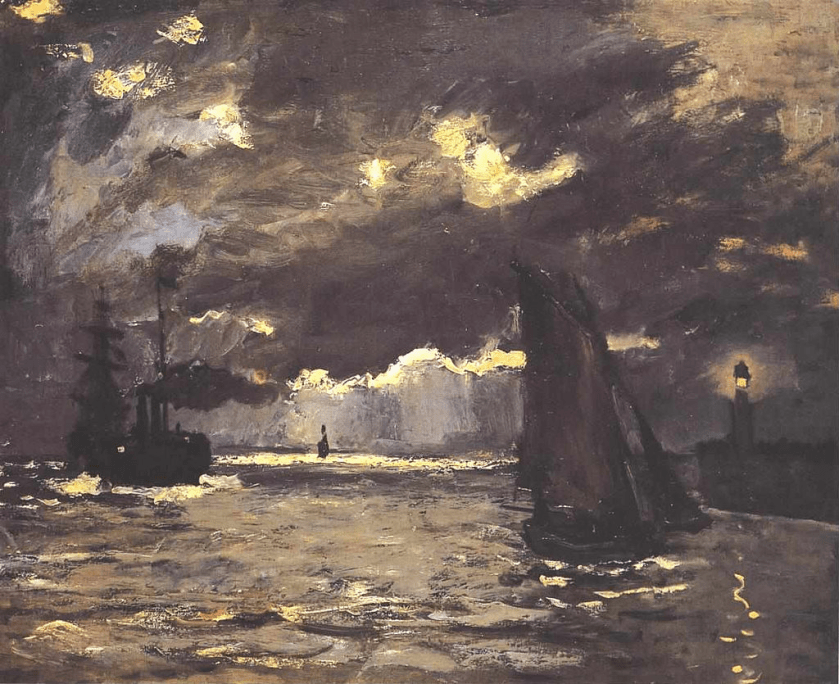

Le paysage se transforme également, devient un miroir qui révèle moins la nature que l’état d’esprit de l’artiste. Turner entremêle les volutes humides et les vagues pour donner à voir les éléments déchainés. L’angoisse étreint le cœur devant ses rafales de vent aux tons fondus. A force d’empâtements, les tourbillons soulevés par Turner au couteau trahissent à l’extrême la fragilité humaine. Pour sa part, Friedrich capture la mélancolie des soleils du nord, des brumes qui enveloppent les ruines d’abbayes et s’enrubannent autour d’arbres décharnés. Chacun de ses tableaux propose une énigme, un chiasme autour des âges de la vie ou une troublante allégorie de la condition humaine. Le poète allemand Novalis résumait en 1798 cet élan qui tend à voir au de-là de l’apparence : « Quand je donne aux choses communes un sens auguste, aux réalités habituelles un sens mystérieux, à ce qui est connu la dignité de l’inconnu, au fini un air, un reflet, un éclat d’infini : je les romantise » Cette démarche lui permet de retrouver le sens originel du monde qui demeure à jamais obscurci aux yeux des profanes. Le réalisme semble alors trivial et ne saurait rivaliser avec la fantasmagorie d’un Fuseli, d’un Blake ou l’idéal farouche, parfois morbide, qu’instille un Géricault à ses sujets. Lorsqu’il aborde les portraits d’aliénés, de 1818 à 1822, Géricault pousse à l’extrême une quête inaugurée avec l’observation de cadavres à la morgue pour son Radeau de la Méduse.

Alphonse de Lamartine composa une ode intitulée L’Homme, dédiée à Lord Byron, celui qui fut tout ensemble l’archange et le démon du romantisme anglais. Ce poème peut être lu comme un manifeste esthétique du romantisme, « Du nectar idéal sitôt qu’elle a goûté/ La nature répugne à la réalité / Dans le sein du possible en songe elle s’élance / Le réel est étroit, le possible est immense. » Spiritualiser le monde, voler le feu sacré aux Dieux, s’élever au-dessus du commun pour atteindre les cimes, ces ambitions reposent sur ce qu’énonçait déjà Swedenborg en affirmant que « le monde physique est purement le symbole du monde spirituel. » Le poète des Méditations utilise l’oxymore harmonie sauvage pour décrire le génie de Byron. Cette figure de style convient aussi aux convulsions puis à la sérénité d’un Liszt, aux flamboiements hallucinés de Delacroix, aux envolées lyriques de Pouchkine face à la mer. Mouvement européen, le Romantisme rassemble sous ses couleurs une génération fascinée par le sens et par les sens, par l’attractivité du néant, par la folie et la grâce, par le bien et le mal, les poisons et la mystique. La création est magnifiée, sublimée tandis que l’artiste hésite sur le fil, entre les tourments de Prométhée et les affres de Satan.

Un tableau réalisé par Friedrich en 1818 représente un voyageur, de dos, au sommet d’une montagne, surplombant une mer de nuages. Cette œuvre est devenue une icône du romantisme. De ce personnage, nous ne saurons rien, ni ses traits ni ses desseins. Il est suspendu pour l’éternité entre l’absolu et la finitude. Le ciel et l’abîme l’englobent, il devient le point focal du tableau qui concentre la grandeur tout autant que la solitude. Le voyage de la vie s’arrête au bord du gouffre. La ligne d’horizon et les crêtes ne sont qu’un lointain écho des montagnes bien réelles de l’Elbe, de même que la Mer de glace qui broie un navire dans Le naufrage est moins un rappel géographique qu’une poignante métaphore. Emu par cette toile, en 1834, David d’Angers évoquera à son propos la tragédie du paysage. Laissons donc Lamartine conclure : « Borné dans sa nature, infini dans ses vœux / L’homme est un dieu tombé qui se souvient des cieux. »

Sophie Rochefort-Guillouet is a professor at Sciences Po Paris Campus du Havre.