By Fabian Haug

All images credited to the author unless otherwise stated.

Just over two years ago, when I first arrived in the Netherlands for college, I couldn’t stop thinking about the lush green forests, waterfalls, and temples near my home in Northern Thailand. I had spent the previous six years growing up in Chiang Mai, and my time there made me feel attached to the city, its people, its culture, and its incredible food. I developed a particular love for Khao Soi, a coconut noodle soup – its thick-crispy noodles, coconut broth, and soft, tender beef are what I craved then, and still often do today.

I remember during my first few weeks in the Netherlands my mind was filled with memories from my time in Chiang Mai—frequenting malls such as One Niman, hiking in the stunning Chiang Dao and Mon Jam mountains, and the silly antics I used to get up to with my friends at school. In short, I was homesick. Suddenly, the small things I took for granted from simple visits to the Seven-Elevens at night to dinners with my parents were experiences that I started missing—something that I longed to experience again. Nonetheless, I believe this sense of homesickness is linked to a deeper truth: it was linked to the fact that I had lost my sense of security.

Looking back, this should seem almost unsurprising. I had just moved to a new city—The Hague—a place I had never visited before, more than 8,000 kilometres away from home. I arrived alone, with no familiar faces, no friends to lean on, and no clear sense of how my college experience would unfold. To make matters worse, the airline lost my suitcase which held most of my belongings—clothes, snacks, and cherished souvenirs from Thailand. While pop culture often paints the picture of moving to college as an exhilarating leap, it is equally vital to acknowledge the immense weight of uncertainty and loneliness that can accompany such a monumental change.

Left to right: A view of the Chiang Dao mountains from my home in Mae Rim, Chiang Mai. My parents Achim and Au after a hike in Mon Jam, taken by me.

However, as time progressed, I made friends, adjusted to life in a foreign country, and adapted to the demands of university academics. Yet this was no short process. I found myself in between friend groups, navigating how to manage my newfound independence. It wasn’t until the second semester that I connected with people who became my closest friends, and who remain so to this day. During this period of discovery, my homesickness gradually faded, and I began to discover who I was beyond the familiar comforts of my parents and my life in Chiang Mai. I deepened my academic interests, particularly developing a love for international law, while also discovering a passion for travel—and testing the limits of my alcohol tolerance. I learned how to live on my own, how to cook—although my friends still joke that I’m a terrible chef— how to navigate taxes and the Dutch healthcare system. I discovered a healthier work-life balance that worked for me.

Above, left to right: My mostly empty college dorm in The Hague just after moving in, walking tour of Leiden (10 minutes away from The Hague) as part of my “Intro Week”at Leiden University.

Over the next two years, The Hague, its people, and my closest friends made the city feel more like home. I felt safe within my close friend group, full of third-culture kids such as myself. There was Demir, a Dutch-Turkish amateur windsurfer; Emilia, a German-American baking enthusiast; and Ferdi, a mischievous Frenchman. There was Gege, a Dutch-Chinese TikToker par excellence; Marianna, a Polish bookworm; and Eva, a Belgian-English record collector. Finally, there was Sebas, a Colombian-Dutch film buff; and Anastasia, a French-born, American-raised workaholic—just to name a few. These are only some of the people who made my college experience unforgettable. With these friends, I travelled to places like Ireland and Belgium, had wild nights in Rotterdam and Amsterdam, shared deep conversations about life, and cooked fantastic meals together.

Moving to university can be daunting, lonely, and full of uncertainty, but it’s also a time to discover more about yourself, build new friendships, and create memories that can last a lifetime. Looking back, I believe it’s important to recognize that building a supportive community and a new sense of security takes time—and there’s no need to pressure ourselves to instantly find our people or fear missing out on events, as meaningful connections naturally take long periods to develop.

Above, left to right: Gege and Emilia on our short trip to Ireland; Ferdi, Demir, and I having a wonderful cooking session.

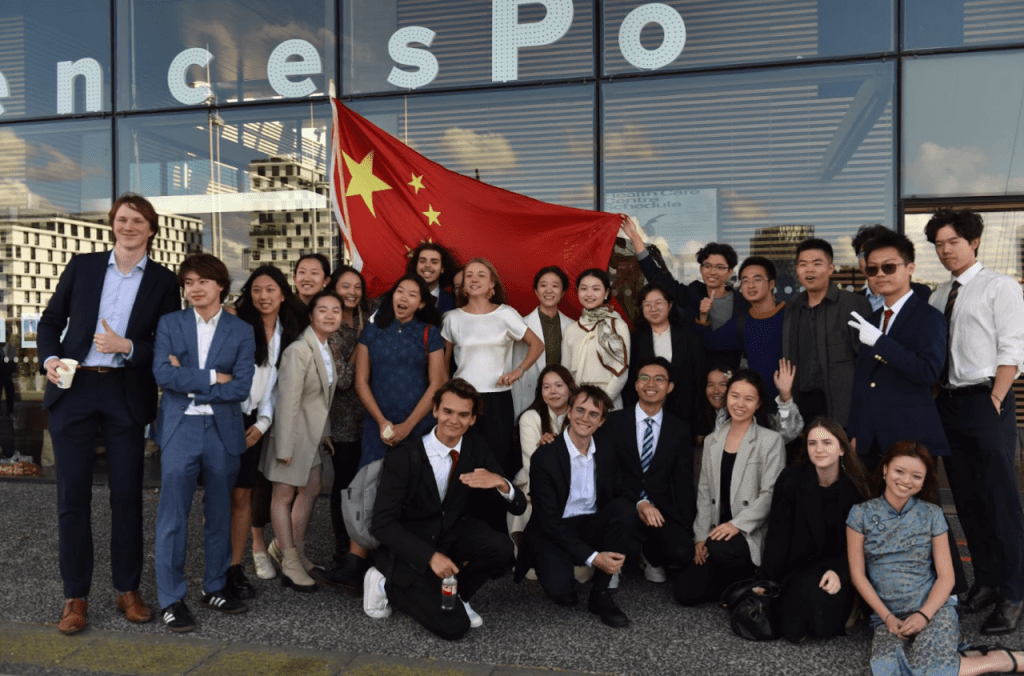

Despite finding a new community, I decided to embark on an exchange semester—which is how I ended up here at the Sciences Po campus in Le Havre. Honestly, I chose to go on exchange partly out of fear of missing out. I felt pressured to study abroad because it was implicitly—though not intentionally—framed by my friends and the university administration as an essential part of the college experience. I worried that not going would mean missing out on an opportunity to meet new people and explore other parts of the world.

Above, left to right: “Floor crawl” (A drinking party on a floor at Leiden University); Me and my fellow resident assistants at the annual Dies Fatalis in 2024 (our university play).

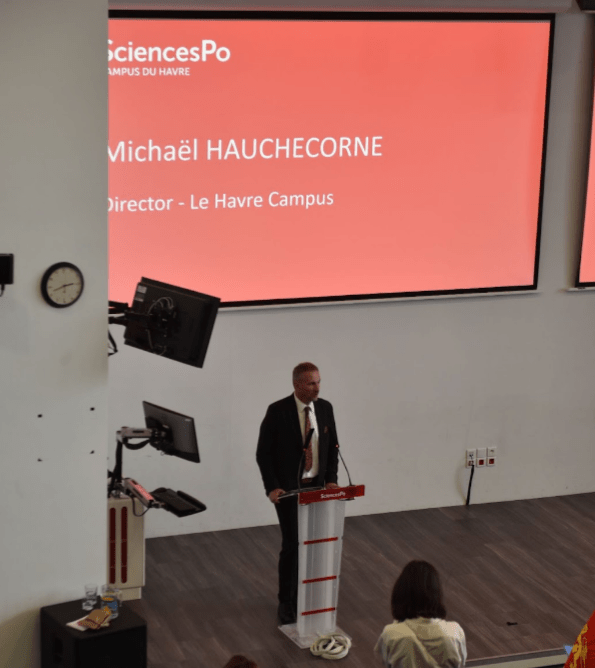

Sciences Po’s campus in Le Havre partly stood out to me not only because of the university’s standing in Europe—but also its small scale and focus on Asia, which I felt was underrepresented in the curriculum of my home university. I remember thinking during the application process “Ohh, the small size of the university is nice, it’ll make it easier to form friendships and build connections.” Moreover, small seminar classes and an intimate atmosphere were what I preferred, similar to my home university, where the campus had only 600 students. The other options I listed on my exchange application were Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the National University of Singapore, located—you guessed it right—in Singapore. These wildly different options reflected my uncertainty about what I wanted from my exchange experience. Did I want to continue studying in Europe? Move far away to the United States? Or stay closer to home and family in Thailand? In the end, Leiden University nominated me to come here to Le Havre for my exchange.

A few months later, on the 25th of August this year, I arrived here, in Le Havre. Again, similar to two years prior I was nervous about the uncertainty of how the experience would go—would I make friends? How challenging would a new university be academically? I was even overcome by a wave of homesickness, an ache, to rewind the clock just a few months and relive the summer. I yearned to experience once more the familiar comforts of home in Thailand. My mind wandered back to the sun-soaked days of adventure, retracing the path through southern Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore—a journey I had taken just weeks before with my cousins, though it now felt like a lifetime ago. Frustration swelled within me. Why did I feel this way—homesick, again—after two years of living on my own in the Netherlands? The feelings seemed unjustified, even childish, and yet there they were, stubborn, pulling me back to a time and place I could no longer touch.

Having grappled with homesickness before, I felt more equipped to face it again. My time in The Hague meant that I knew myself better. While I understood that I needed to step out of my comfort zone to forge meaningful connections with others. I also knew that when I felt down, a short run was an effective way to cope. An occasional tub of ice cream paired with a Netflix show offered a much-needed escape from the strains of daily life, while calls to my parents or friends and the comfort of Thai food eased my longing for home. Yet, I was acutely aware that I would only be here for four months—would that be enough time to cultivate a sense of community? After calling a friend in Bangkok, he suggested approaching this experience with the mindset of trying to make the most out of every day. We should try to take steps to actively cultivate memorable experiences with those whom we care about, but most importantly, we should treat others the way I would have liked to be treated when I first moved to university two years ago. For me, it meant someone inviting me to activities, showing they cared, and checking in on me—even if I didn’t always share how I was truly feeling.

So, how has my integration at Sciences Po been so far? I’d say it has gone faster than I expected. In just over a month, I’ve built close friendships and made memories that I know will stay with me. I’ve found common ground with many people—whether it’s bonding with fellow exchange students over the challenges of Sciences Po’s administration and navigating CROUS housing, or sharing conversations about Thai cuisine and culture with my Thai and Southeast Asian peers. As a half-German, I’ve bonded with other Germans over our shared love of German bread and the occasional indulgence in complaining—though I’ve learned to keep that in check, as too much can dampen my mood. However lately, our conversations have shifted to our deep affection for French pastries, revelling in the delightful flavours and treats that have quickly captured our hearts now that the initial shock of moving to France has worn off. I’ve made it a priority to invite as many people as possible to join me on runs, and I’ve embarked on spontaneous trips to Honfleur and Cap de la Hève. These experiences have allowed me to forge meaningful connections more swiftly than I anticipated.

Above: Zo-ren, Audrey, JJ, Sylvian and I on our spontaneous trip on Honfleur

Nonetheless, it has not always been smooth sailing. I’ve faced moments of academic stress and occasional loneliness when feeling overwhelmed, and I haven’t been perfect in going out to connect with others. I’ve aimed to treat others as I would have liked to be treated when I first moved to college, yet there were days when I found myself retreating into my comfort zone instead of “making the most of it” and fully embracing the opportunity to spend time with my newfound friends. But I think it’s important to emphasise that this is okay—it’s perfectly fine not to always be on top of things. “Making the most of it” also means allowing ourselves space to relax and not forcing ourselves into social situations we’re not ready for or don’t want to be in.

Above, left to right: Southeast Asian Gang at WEI; late-night run.with JJ and Zo-ren

With these thoughts in mind and drawing from my personal experiences, I’d like to share three takeaways on how we could approach integration more healthily with greater compassion and understanding.

- Homesickness, uncertainty, and loneliness that can accompany moving to college is natural—and we should approach others with compassion and care and acknowledge that this can be a difficult time of transition.

- Building friendships takes time—meaningful connections typically don’t happen overnight. We shouldn’t pressure ourselves, as friendships tend to develop naturally over time. Nonetheless, this does not diminish our power to engage with others, invite people for activities, and seek meaningful relationships.

- Take the time to explore what self-care looks like for you—university is a journey of self-discovery and personal growth. We should try to identify not only what activities can help us de-stress but also the types of social situations and friend groups we genuinely enjoy spending time in.

Yet I do want to emphasise that these insights are drawn solely from my own experience; you and others may have wildly different experiences based on your individual journeys. Nevertheless, I hope you can find something relatable in this reflection—perhaps a truth that will help guide you, just a little, toward a more fulfilling college experience. I hope these experiences can offer you some encouragement as you navigate your own paths.

With love,

Fabian