“If space-junk is the human debris that litters the universe, junk-space is the residue mankind leaves on the planet.”

This quote by architect Rem Koolhas confronts you as you enter Jean Castorini and Vinzent Wesselman’s exhibition The Production of Destruction. The paradoxically titled exhibition attracted a steady stream of curious visitors to its opening on Monday evening. Clutching cups of cider and walking around the gallery in a low buzz of voices, groups took in the powerful assemblage of modernising urban scenes in South East Asia and glacial landscapes of the Arctic.

As a self described visual metaphor, the photos are curated to elicit a sense of dissonance between the two environments and spark conversation on the nature of modern industrial consumerism and the effect it has on the natural world. Framed in the heat of a political climate that remains deeply divided on climate change, the photos contribute to an ongoing discussion that questions the man-made construction of the urban environments we inhabit and the negative effects their creation has on natural spaces from which we are sheltered. The stark juxtaposition of the two settings immediately brings to attention their subtle symbiosis, as photos of rapidly retreating glaciers are placed next to those depicting rapid vertical urban expansion. The images present incredible glaciers that are formed over centuries, and highlight how they are now deteriorating simultaneously with the proliferation of new skyscrapers- an unlikely but powerful predator of these ancient ice forms.

The exhibition also acknowledges the people who inhabit these places. A photo of soccer pitch nestled between mountains and an ocean speckled with icebergs. A transitory looking church in a Inuit town. A discarded gold religious relic amongst a pile of rubbish. A handless statue of Madonna. Reflections off the ocean, and off shiny skyscrapers. Through the presence and lack thereof of modernisation, we are given a clear expression on mankind’s differences.

Castorini and Wesselmann’s exhibition brings a collision of two continents into a 30 square metre gallery in Le Havre, that forces us to confront the truism that our behaviour in urban settings has immense impacts at the poles of the Earth. The

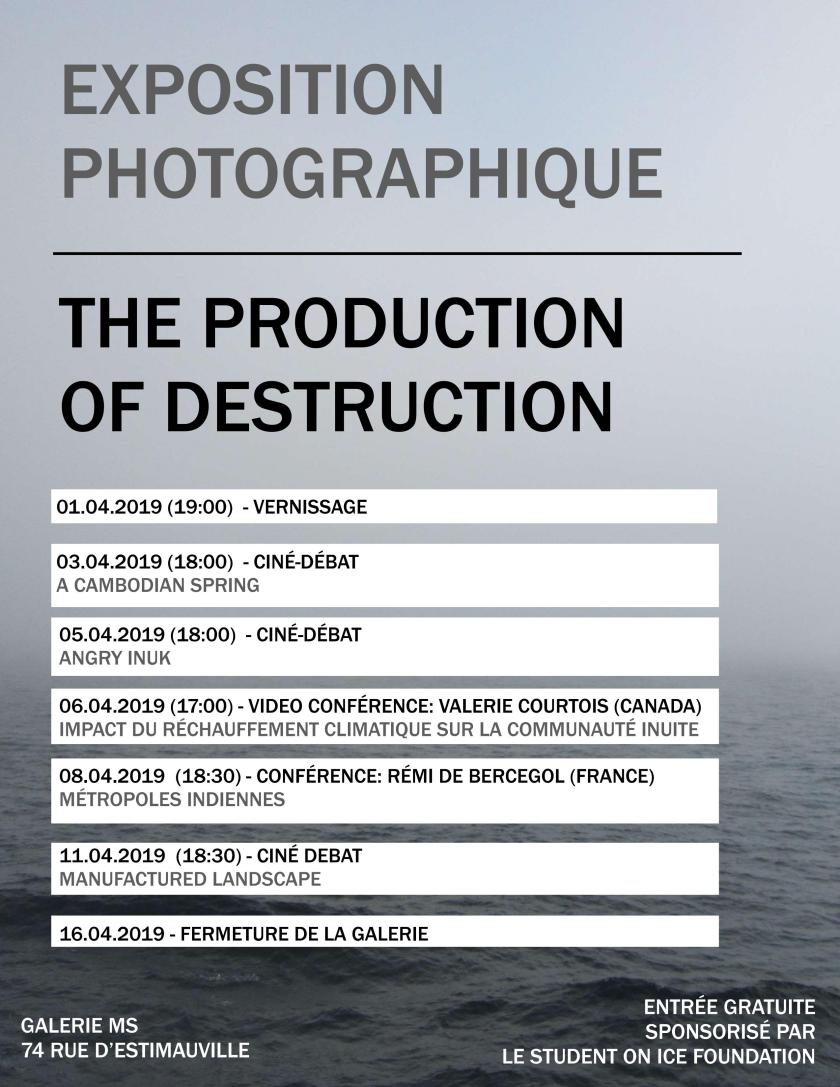

Production of Destruction is a thoughtful collection of photos that give insight into a global concern. The gallery’s program for the coming fortnight is a promising lineup of debates with guest speakers and film screenings that will continue the discourse on the most significant issue of our generation.

See below for a full schedule of the upcoming programming. The exposition closes on the 16th of April.

Joyce Fang is the Public Relations Manager of the Bureau des Arts and a reporter at Le Dragon. She is covering an exhibit by second-year students, Jean Castorini and Vinzent Wesselmann at Galerie MS.