By Anh Nguyen

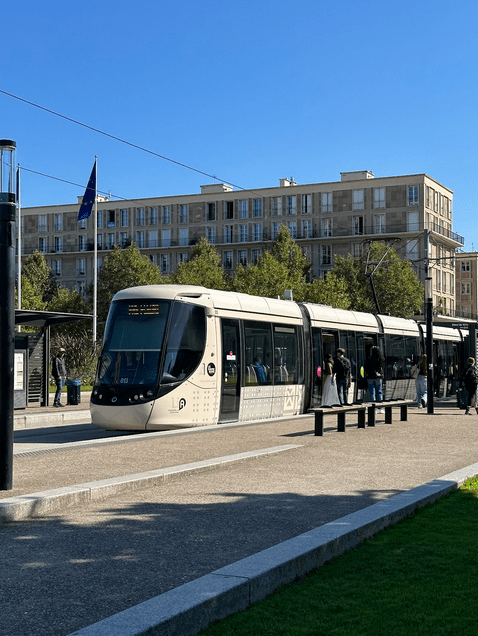

Smoke caused by industrial actions at the docks in Le Havre, as observed from Sciences Po Le Havre’s Grand Amphitheater. Taken November 2024.

Photo credit: Fatine Mohattane

On the morning of November 4th 2024, students of Sciences Po’s Le Havre campus arrived to an unusual sight—thick black smoke billowing from the docks. The sight of port workers setting fires in protest drew classroom activities to a pause, eyes drawn to the rising haze. It turns out that while we debated French politics in classrooms, a real battle over labor rights raged right before our campus. As of February 2025, the effort continues. As the newly-established French government, headed by François Bayrou seeks stability, labor rights and pension remain at the heart of national debate. The student body of Sciences Po’s Le Havre campus, given its political activity, rigorous coursework in French politics, and sustained interest in maritime issues, would therefore benefit from having a clearer grasp of this development and how it is situated in the larger scene in French politics.

Since mid-2024, workers in the ports both of Le Havre and of Marseille have been engaged in industrial action, primarily in opposition to the French government’s pension reforms. Led by the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) – one of the most influential trade unions in France – protests began as sporadic strikes, with workers blocking access to key terminals at the Port of Le Havre. The smoke from burning tires and pallets – visible from Sciences Po’s Le Havre campus – became a regular sight in the city as workers voiced their discontent with the government’s pension overhaul. By December, the protests turned into more coordinated displays of action, with mass walkouts and disruptions across multiple terminals.

These actions have continued, although less visibly to the spectators in Sciences Po’s Le Havre campus, since the recent return of students from winter break. In January, the protests continued with four-hour walkouts on four days and 48-hour strikes in late January. These actions further disrupted port operations, leading to delays in cargo handling and shipping schedules. At the time of writing this article, February 2025, industrial action has persisted through similar mechanisms, in alternating days throughout the month.

This industrial action is a response to President Emmanuel Macron’s government’s ongoing series of pension reforms, which include the increase of the retirement age from 62 to 64 and changes to the way in which pensions are calculated. It thereby extends the working life of many French workers, especially disproportionately affecting those in high-risk, heavy-labor professions. This includes dock workers, public servants, and transportation workers, who typically benefit from early retirement due to the physical demands of their jobs.

The pension reform is part of Macron’s broader economic agenda, by means of which he has positioned himself as a centrist reformer who seeks to push for structural changes to make the French economy more competitive and sustainable in the long run. The pension system, functioning in a pay-as-you-go model, has long been viewed by economists as unsustainable due to France’s aging population and high public debt. The government argues that the reform is necessary to ensure the financial health of the social welfare system, by unlocking billions in funds to narrow a budget deficit, and maintaining pension stability. Since its passage in the Constitutional Council in 2023 through the invocation of article 49.3 – allowing for the passage of the reform without a parliamentary vote – it has sparked nationwide protests and strikes, and has constantly been adjusted as the government alters between improving its fiscal savings and accounting for public demands.

As France’s second-largest port, and a vital gateway to global trade, Le Havre is an economic engine that fuels the national and European economy. Handling nearly 60% of France’s container traffic and integrating into the Seine Axis, it connects industries to markets inland and across North America, Asia, and Africa. Thus, industrial action in Le Havre reverberates far beyond its docks: blockage of ro-ro, bulk, and container terminals, resulting in the cancellation of ship calls and significant delays in vessel schedules, imposes cascading effects on supply chains, proliferates costs, and impacts various sectors reliant on timely deliveries. In December 2024, the number of vessel arrivals in Le Havre decreased by 21%, with 169 calls recorded, necessitating commercial rebates and tariff discounts for container lines by the union of French ports Haropa. Given similarly intense industrial action in other major ports, in Marseille and in Normandy, and given their economic linkages, disruptions in these ports have affected industries and employment across the nation and beyond.

More importantly, industrial action of port workers in Le Havre has come at a critical time, as pension reform remains a matter of key contention in French politics. Budget deficit has always been a focal point of controversy in recent years. This is observed through the 17 attempts of motion of no confidence over the pension reform, the invocation of the much contested constitutional article 49.3 for the passage of pension-related matters, and the recent collapse of the Michel Barnier-led government in 2024 over a budget standoff.

For the newly-formed, minority government under the centrist Prime Minister Francois Bayrou, pension reform remains key as it lies at the crossroads of differing positions on the political spectrum. Actions his government takes upon this issue would thus determine whether it gathers a more stable majority. It has notably attempted to do so, with Bayrou recently announcing the renegotiation of this pension reform, essentially a hand stretched out towards the left to secure a more stable government.

Given the time sensitivity, intensity, and large-scale impact of the industrial action of port workers in Le Havre, the course of pension reform policy in the recently formed French government may still be subject to change. This industrial action thereby offers a pertinent, ongoing exemplar for Sciences Po students of the Fifth Republic’s executive mechanisms, loopholes, and the French current political scene at large.