Our beloved Sophie writes a paper on the role of fans in different cultures.

Hand fans have very practical reasons to exist. They are used to create a small cooling breeze to refresh people but also to chase away flies or any other pest insects and finally to fan flames. At the very beginning, tree leaves, bamboo sticks, a piece of bark were used for this purpose. Later on, the use of fan developed worldwide and using a fan became a sign of social position, all the more as they became lavishly adorned and thus highly fashionable.

The existence of hand fans in Africa or in the Americas has been proved thanks to travel logs. For instance, when Christopher Columbus came back from India, he presented the Spanish royal couple with six hand fans, on behalf of the Aztec people. There are also early evidences of the presence of fans in Africa, especially when we consider Egyptian carved reliefs and artifacts adorned with ostrich feathers (Maat symbol), or when amazing metal carved fans were discovered in Tutankhamen’s tomb. Other styles of fans were found in Sudan, made of peacock feathers, some being a thousand year old.

We will however concentrate on two continents: Europe and Asia and focus mainly on social etiquette and elegance.

I/ Asia

- History of Hand Fans

In the first Chinese dictionary, complied in the 2nd Century CE, a fan is interpreted as a door panel that hung from the ceiling. This type of fans became known as the Chuke fan. There was however fans made from different types of feathers and this is the reason why the word for hand fans is the same as feather. According to the type of feathers used, you could determine the social status of its owner: goose feathers were for common people whereas peacock, cranes or pheasants feathers were used for the sake of the gentry. The Pien Shen was also used; it was a simple one, not fit for ceremonies. Anyone could make one with woven leaves or bamboo. They are referred to in Chinese literature since the 1st century BCE.

The practice of writing or painting on fans is also recorded very early. A companion of the emperor Ch’eng of the Han dynasty, around 33 BCE, wrote poems and lyrics on fans. During the Sung dynasty (960-1279 CE) painted circular fans became popular at the Court and among the nobility. It is during that period that folding fans were introduced in China from Japan. They were called wo-shan, referring to Japanese fans.

Gradually, but especially under the Yuan and Qing dynasties, artists started to use fans as artistic supports and, in the 16th century, they would start signing them. The Three Excellences of the Chinese art were applied to the decoration of these fans: painting, calligraphy and poetry. The materials used were mainly bamboo, whale bone, iron and ivory for the ribs and paper for the leaves. Leaves could be changed but the ribs were seen as valuable when their patina was aged by the handling. They would be treasured in families.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, most of the production of hand fans was sent to Europe as they were so much in demand. These decorated fans corresponded more to a western taste than to a Chinese one. At the turn of the 20th century, the Chinese Empire collapsed and a Republic was born after years of turmoil. This was thus depicted on hand fans, as testifies the hand fan made by Chinese artists in reaction to the Tientsin events. Colons asked the governor to stop the diffusion of this hand fan that was nonetheless duplicated in many copies.

In the 1960s, because of the Cultural Revolution launched by Mao Zedong, many hand fans were destroyed as mere vieilleries and their cultural and social hierarchy aspects were despised.

The material trace of the first hand fan in Japan is on a wall painting in a burial mound dating from the 6th century in Fukuoka. This type of fan, a flat one, called Uchiwa, probably came from China, passing through Korea.

A century later, Japan invented folding fans, mostly for women, which were composed of 39 ribs[1] One night, during Empress Jingu’s reign, an artist paid great attention to a bat that was opening and closing its wings. It gave him the idea of a more practical fan: the folding fan. This first fan was called komori or bat. They were made from slips of Juniper wood, sewn together at the top with a string and tied together at the other end so that they opened in a radiating way. The oldest surviving paper folding fan is documented as dating from 1188.

The first literary reference to this folding fan was found in the Japanese dictionary compiled around 935 that lists two types of fans, the Uchiwa and the Ogi. It rapidly became a desired work of art at the Court. The fan developed in this part of the society was called Hiogi and was made only for the sake of the Tenno. However, the nobility eventually used it. It was composed of 34 to 38 wood blades and the particularity was about the rivet[2] that had a bird shape on the obverse[3] and a butterfly shape on the inverse[4]. Painters used bright colors to depict brightly animals, nature or landscapes.

As well as in China, during the 18th and 19th centuries, Japanese fans evolved with the apparition of trade (even though limited and controlled till the end of the Edo period[5]) with the West. The ribs and guards were more adorned. Hand fans also became really popular in the Japanese high society and there was almost a Fan-mania. In order to preserve society from any conflict or high society from any bankruptcy, the Tokugawa Shogun decided in 1701 to forbid the fabrication of too valuable hand fans. Folding hand fans became the symbol of a sophisticated lifestyle to the Japanese – as the radiant ribs were seen as the sun dawn. The rise of the Ukiyo-e prints, pictures of the floating world, depicting daily life scenes had great success in Japan and soon abroad as well. It was not really expensive, considered as craft more than art at first, and it was easy to buy prints from street vendors who had many for sale. Ladies holding fans were featured in those prints, especially by Hokusai, Harunobu, Utamaro or Hiroshige. Portraits of beauties (Bijinga) depictions of warriors or Kabuki theatre characters include fans as a common accessory.

At Cambodia’s peak – the period of the splendor of Angkor – fans were also used. Indeed, we can see – on some Khmer bas-reliefs – large fans used to refresh the king or even military officers. Wooden fans could be also found in what is modern day Malaysia.

In India, hand fans were, as in China, called after the word feather, or bird’s wings: pankhas. Indian fans were various in their uses and materials. There were fixed fans, which are held to fan, revolving fans, which can be shared by people sitting and enjoying the cool air and lavishly decorated royal fans, which are shaken by strong men and used to fan large congregations of people in the rajahs or maharajahs’ courts. There were also small ritual fans, which were used daily to fan the statue of Krishna, fly whisks, which were used to fan the Sikh holy book at gurudwaras and those which were used in mosques during Muslim festivals.

- Numerous uses of Hand Fans

- The Three Excellences plus one

Dance: In Japan, as well as in China, fans were used in artistic performances. The Japanese Noh actors, professional dancers and then geishas became masters of elegance. Any position of the fan would describe a precise word, just like hands and fingers in Cambodian or Indian dance. The hand fan could successively represent a bird, water or even a tree. In China, fans were used in many types of dance, including Ping Tan (Chinese storytelling, usually accompanied by musical instruments) and Quyi (story telling with music and performances). There are many favorite poems about fans and its different meanings during a dance. “Waving a feathered fan, wearing a silk handkerchief, he joked and smiled; and reduced the enemy’s ships to flying ash and smoke.” These words show confidence of the character, expressed wittily in a natural and unrestrained style. “Holding a round fan while bowing with clasped hands is like holding a full moon; waving a fan to feel the embracing wind.” The expression this time shows precision and gracefulness. The fabrication of dance hand fans was quite particular. In order to be more practical during dances and throws, the gorge was weighted, meaning that some metal was added.

Painting: fans were also convenient supports for painters. Landscapes, gardens and scenes de genre were highly praised.

Calligraphy: according to a Chinese legend, the first calligrapher who used hand fans as a canvas was the famous Xi Zhi Wang. When going to the little city of Shao Xin, he saw an old woman desperately trying to sell bamboo hand fans; he told her that he would write characters on them so that she could gain more money. This is what happened and the success gave incentive to calligraphers to use hand fans as a support. The Tang emperor Tai Zhong was a great calligrapher and offered his officers fans he wrote on as a present during the Dragon Festival.[6]

Poems: hand fans were both a support for poems and a topic for poem. For instance, a famous hokku from Sokan[7] says: « In the full moon/ if you adapt a stick / a beautiful fan.”

- A representation of social rank and politeness

Having a carved wooded fan, or a refine silk fan was synonymous of wealth and a certain social status. Fans were used both by men and women in Japan. At the Japanese Imperial Court, the handling of fans was part of the etiquette. Women were taught to use it in the proper way.

Holding a hand fan is also a sign of respect. If we do consider the tea ceremony, in Japan, we notice that the guest will always come to the tea reception with a folded fan before him. It symbolizes the traditional barrier between the guest and the tea master.

Once more we are going to focus on China and Japan, where hand fan is commonly used in wrestling sports.

In China, it is used noticeably during Kung-Fu matches. It is a tool used to protect oneself from hits and give some hits as well. Indeed, you could prevent your adversary to see what kind of punch you would give him.

In Japan, hand fan are employed during Sumo fights. The judge or referee of the game, also called gyôji, would get a fan out of his dress and present it. It is part of the ceremonial that when he turns it on the other side, the game can start. According to some historians, the ancestor of the hand fan was called the gunbai, which was a war fan. It is mostly made of plain lacquered wood. At the end of the game, the gyôji will use the fan to point out the winner and to put on it the envelope containing the award.

Wars: In Japan particularly, fans were tools used by commanders to lead their troops. They are called gusen. On horse backs, commanders were at the head of the soldiers. To make subordinates understand their will, the fan was really a practical device for samurais. (Remember a famous scene in Kurosawa’s Kagemusha). There were two sorts of gusen: folded fans in metal and wood fans that actually looked like panels fitted into a stick. The folded fan often depicted a rising sun, symbol of Japan. A description survives of Hacheman-Taro’s Gunsen: “In front with mica fold sun device, the reverse with mica and a silver moon device […] 12 bamboo sticks lacquered black and heavy with a metal oya-bone (guard).” When it was opened, it meant that the direction showed should be taken or it was a sign of rallying. When it was closed, it was a symbol of protection, and a warning to stay on guard.

Weapon: fans could also be transformed into powerful weapons. In Japan, they were called tessen. The frame was made out of iron, a strong metal able to pierce the adversary’s armour. Their creation is due to the prohibition of weapons in different places such as tea houses, or temples. In order to react in any case, an invisible weapon had to be created: a metal hand fan. Men and especially women had them in their sleeves.

Trial: in China, fans were used by judges while sitting in court of justice. After listening to the defendants and the victim, the judge would pass judgment. One by one, the leaves of the fan were folded and the sentence was set. One can see a specimen of this kind of fan dating from the 19th century in the Fan Museum in Paris.

Propaganda: Fans were a support for paintings as previously mentioned but also for song lyrics that were not always too kind or nice to the government. The positive point was that you could fold it and closed quickly if authorities were around.

Buddhism: During the studying of the precepts, meaning that – as a biku – you are on the path to become a Buddhist, a priest would give you a new name and either a bead necklace or a fan on which your name would be written. In Myanmar, hand fans, called yap were and still are one of the only material things a monk can possess.

Shinto ceremonies: in the Shinto rites, Kaguras are ancient shamanic dances. In the oldest one, called Miko Kagura, which is still practiced as a heritage dance nowadays, the dancer uses bells and hand fans to make circular movements with emphasis on the four directions. It was meant to appease the spirits from the North, South, East and West.

II EUROPE

- History of hand fans

The presence of hand fans in European culture is both an original invention and later the result of trade with Asia. Europe had obviously, since Antiquity, knowledge, crafts and use of hand fans. In Greece, Tanagra style terracotta statues represent gracile ladies with spade shaped fans. A huge fan would be used to provide fresh air in Roman circus when games were held. Anthony Rich, in le Dictionnaire des Antiquités (1883) wrote that hand fans of Greek and Roman ladies were made out of lotus leaves, peacock or ostrich’s feathers or any material of this kind. They were not brisés[8] but straight and had long handles as slaves were appointed to shake them.

During the Middle-Ages, in the Italian peninsula, les dames élégantes appreciated particular hand fans, today called screen fans, shaped like a flag hold on a stick. It was used by most of the population, without taking into consideration social rank. As the early Tanagra statuettes, women depicted in paintings, clad in sophisticated draperies were often holding fans.

During the Renaissance, European countries sent around the world navigators to develop seaborne trade, to find new markets and new resources, to promote Christian faith and to learn more about the unknown. Fans were luxury goods that would soon be much in demand in Europe. Importation of hand fans from Asia to Europe started after their introduction thanks to traders and religious orders from Chinese East coast. Importations were mostly to Spain and Portugal at the beginning but were also an incentive to create new types of hand fans. Little by little, fans from Asia would be appreciated gifts and trinkets a woman of taste was to have among her fashion accessories[9].

Elizabeth I of England and later the courtesans in Versailles popularized this object which was also seen as an expensive and prestigious work of art. Under the reign of the Sun King Colbert organized the production, creating “la corporation des éventaillistes» on February 15th 1678.

- An incredible development

Hand fans were to be popular during the 17th century. Mostly in France and Italy, they would be used as supports for reproductions of famous painters and engravers’ works of art. Folding fans will be more appreciated than fixed ones. Technically speaking, leaves will be done not only with paper but with skins – noticeably swans’ skin- which make them more resistant. The monture was adorned with ivory and little by little, carvings and mother of pearl marquetterie emerged. Some were even made in precious metals, golden coated or inlaid with pure gold or silver. It was however a luxury fancy object, reserved to nobility and royalty.

It is amusing to notice that at that time, the fans were decorated on both sides. The high society parents gave classical education to their daughters and they wanted everyone to know how learned they were. Thus, the delicate flowers, such as roses and tulips of the obverse, were relegated to the inverse –the part of the fan that the young ladies could see- and replaced by mythological or historical scenes for everyone to behold. It was a sign of how educated the young women were. Yet, behind a fan, you could also mock, whisper, giggle and gossip unchecked.

In the 18th century, Europe produces high quality hand fans but importations, noticeably through the East India Company, were extremely important. Chinoiseries were highly fashionable. Beautiful as they were, many people did not realize that these fans were produced by the Chinese artists to please ‘barbarian’ tastes and were not used by Chinese themselves, as for example the ‘thousand faces’ or ‘mandarin’s fan. It is at this period that the creativity concerning fans developed the most in Europe, differently according to the countries. On the 1st of December 1783, in the Jardin des Tuilleries in Paris, the first hot air balloon was sent to the sky by the Montgolfier brothers. In France, then, every gift à la mode had to be à la ballon. Thus, balloons were drawn on événementiels hand fans!

In Italy, for instance, from the 1770s onwards, most fans were painted with classical ruins, in Pompeian decoration and antic style. There were also dramatic views of Vesuvius erupting and of the bay of Naples. However, they could represent many topics: military victories (Nelsons’ in England) or game instructions (How to play Whist and not lose your temper at the same time…). A ‘hand fan code’ was created. The 18th century is also the century of the French Revolution, which allowed printers to use hand fans as a mean to spread information. At the end of the century, hand fans were available to all the society strata as picture printings developed and lowered the production prices.

- A modern decline? And a revival.

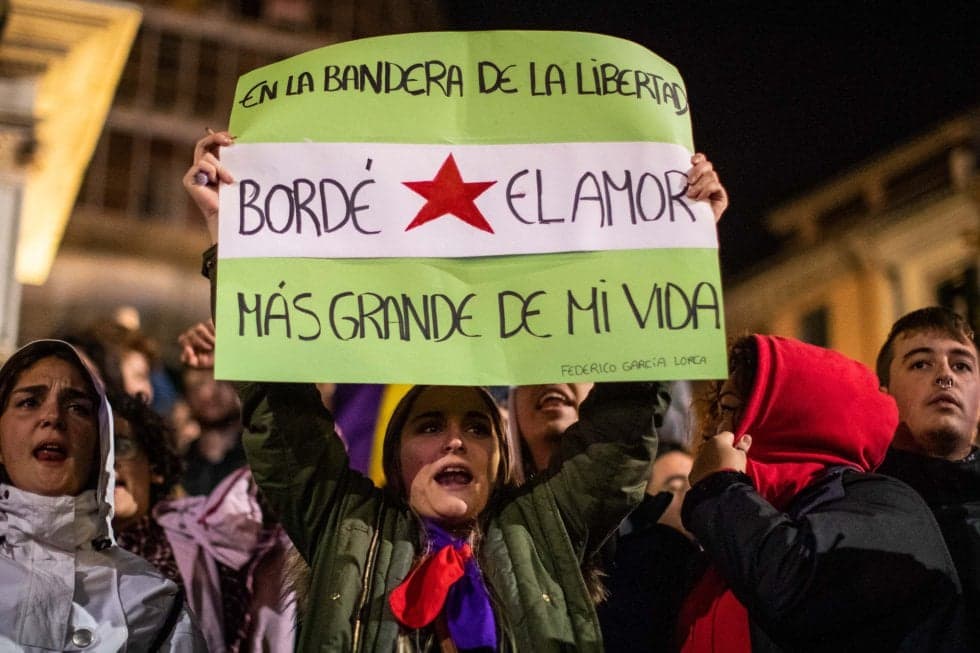

In the early 19th century, the fan size diminished and, during the Restoration, there was many brisés, mainly made from horn and ivory, feebly decorated. Nevertheless, we can still find real jewel fans and extravaganza. In France, hand fans were used to mock Napoleon. Spain, that did not really produced fans but imported them, started its own fabrication. They depicted corridas and pastoral landscapes. Spanish women were really attached to them and the complicated handling would be soon used in Flamenco and Hispanic dances in general. Théophile Gautier, in «Voyage en Espagne” (1843) wrote that he hadn’t met any woman without a fan during his journey. To his amazement, they could have satin shoes and no socks but they had an elegant hand fan[10]. A beautiful Spanish tale recalled two girls who used a fan, one who was nice and sweet would become more and more beautiful as she refreshed herself but the other, selfish and cruel, would become uglier and uglier by doing so. The magic fan would reveal indeed moral beauty or flaws.

This was also a period for international exhibitions. The Crystal Palace exhibition was first held in 1851 in London and many fans, both exhibition fans, and advertising/souvenirs fans survived. Still in 1931, during the Colonial exhibition in Paris, thousands of hand fans would be given freely as tokens, advertising for brands or depicting in an exotic way the remotest territories of the French Empire. A fan would be a beautiful gift for a wedding present or a birthday keepsake. This is the clue to understand fully the plot in Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s fan, a play first performed in London in 1892.

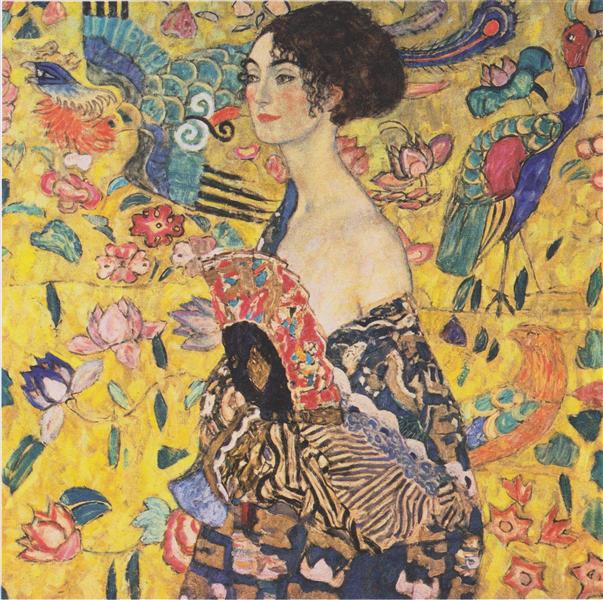

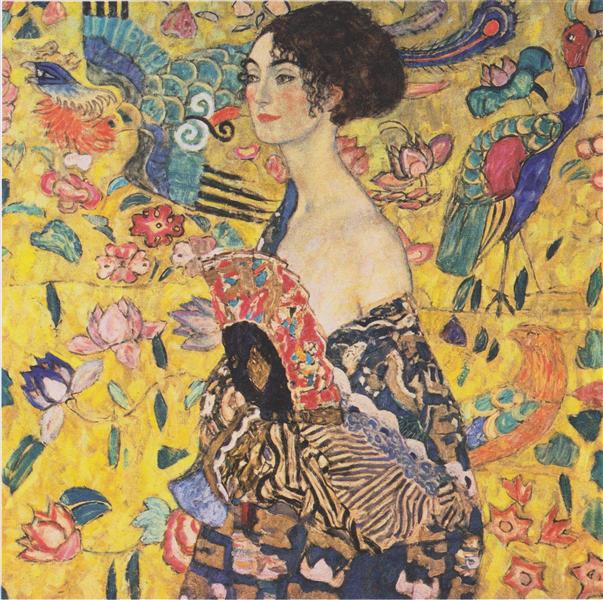

Japonisme would also lead to have fans depicted in paintings as in the famous portrait by Monet of a dancing lady (his wife) in an embroidery kimono. Edouard Manet, Auguste Renoir painted on éventails while Camille Pissarro designed and illustrated dozens of them. We also know 26 hand fans painted by Paul Gauguin on silk canvases. Art Deco artists would also produce intriguing feminine statues. It was but a swan song.

At the turn of the 20th century, as Le Petit Echo de la Mode would provide testimony, the hand fan would decline and soon wouldn’t reign anymore in celebrations and salons. After the First World War, this trinket or babiole was almost forgotten as women emancipated. However, haute couture creators tried and gave the hand fan a re-birth. It is noticeably the case with Christian Dior and his Spring Summer 2007 collection. Not to mention Karl Lagerfeld personal iconic display of fans.

- Use of hand fans

- Proof of a social rank & sign of fashion

It was very often used between the 17th and the 19th century more for what it could represent than for the practical purpose of providing ladies with cool air. The quality of the hand fan, meaning the materials used to make it, the author of the leaves painting and its origin determined the value of it and thus, the social rank of its owner. The more valuable the fan was the highest rank the owner had. Those coming from the East were seen as treasures, because they were rare and exotic. Some made in Europe, by the designers of Maison Duvelleray & Alexandre, in France, were really appreciated. Until the development of printing machines on material, only the nobility and the upper middle class could afford such fans.

Hand fans were part of a lady’s corbeille de mariage. In the Fan Museum of Healdsburg, a French fan is painted with garlands of gold roses, Venus attended by Cupids and an empty birdcage with an arrow. Hand fans started to be collected and the Duke Augustus of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg was one of these hand fan fans. He bought them thanks to a certain Mr. Meyer in England, as their correspondence testifies. It is also said that on the eve of his wedding to Queen Victoria, his grandson Prince Albert presented her with four fans, which she referred to in her diary and treasured afterwards.

A 18th or 19th century English lady of the aristocracy class would have a whole collection of fans: fans to use in the morning, fans to use in the afternoon, fans to use at charities or galas, concert fans, ball fans, black and grey fans to use when there was a death in the family. The fan was the continuation of the wrist and hand. Its handling was a proof of savoir vivre.

In reaction to the strict moral code, in Europe, meaning that each individual had the duty to seek salvation and to live consequently and that courting and romance were forbidden, a secret code little by little appeared in Spain and would be used in France, Italy and the rest of Europe. It was a secret code – as les mouches on a white complexion – to flirt secretly.

Here are some examples :

- Hold it in the right hand in front of theface : follow me.

- Hold it in the left hand in front of the face: I would like an entrevue.

- Make it slip on your cheek: I love you.

- Make it slip in your hand: I hate you.

- Present it closed: do you love me ?

- Put it on your lips: kiss me.

- Put it on your left ear: I would like you to leave at once.

- Make it turn in your left hand: we are spied.

- Make it turn in your right hand: I love someone else.

- Hold it in your right hand: you are asking too much.

- Hold it in your left hand : you have a chance to touch my heart.

And a lot more to convey messages: I’m a married woman, I am engaged, you are cruel, come and talk to me…

A 17th century English writer, Joseph Addison, wrote: “Men have the sword, women have the fan, and the fan is probably an effective weapon too.”

- Propaganda & advertisement

Fans, after the development of printing machines for materials were easy to manufacture, distribute and sell. Since that time, fans would be used in France during the French Revolution (republicans and patriotic fans on which decrees were written or symbols… or royalists’ fans with the royal family members ‘portraits), for the anti-Napoleonic propaganda, for advertisement, to support French troops during the Tonkin war and more.

The word fan, meaning a sporty devotee comes from hand fans. Fans were given to spectators at sporting events. The use of the word “fan” is thought to derive from the word “fanatic” but some are adamant that it is only because of a 19th century baseball writer who used it to describe all the audience waving supporting hand fans.

In orthodox churches, fans (called ripidion), as well in catholic churches, fans (called flabellum) were used to announce the holy wafer procession, the coming of the pope or of dignitaries. It was an honorary gesture towards the “successor of Peter”, directly coming from the roman imperial protocol. In the Apostolic Constitutions, written in the 4th century, we can read (VIII, 12): “Let two of the deacons, on each side of the altar, hold a fan, made up of thin membranes, or of the feathers of the peacock, or of fine cloth, and let them silently drive away the small animals that fly about, that they may not come near to the cups”. However, if it is still use in orthodox churches, it was forbidden in Catholic tradition by the second council of Vatican

Fans were seen traditionaly as vanity objects and therefore had to be renounced to by christian girls aspiring to sanctity.

To read further:

Avril Hart and Emma Taylor, Fans, Victoria and Albert Museum publishing, (V and A), London, 1998.

Anne Sefrioui, Éventails Impressionnistes, Citadel, Paris, September 2012 (along with the Musée d’Orsay catalogue on the temporary exhibition held on Impressionism and fashion in 2012).

Maryse Volet and Annette Beentjes, Éventails, Editions Slatkine, Genève, 1987.

Michel Maignan, L’éventail à tous vents, Louvre des Antiquaires, Paris, 1989.

Musée de l’éventail, 2 rue de Strasbourg, 75010 Paris.

Online exhibition : the art of folding fans: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/arts-and-crafts-museum-hangzhou