A report and analytical defense of the global climate strike.

“Many social, technological, and nature-based solutions already exist. The young protesters rightfully demand that these solutions be used to achieve a sustainable society. Without bold and focused action, their future is in critical danger. There is no time to wait until they are in power.”

Science, 2019

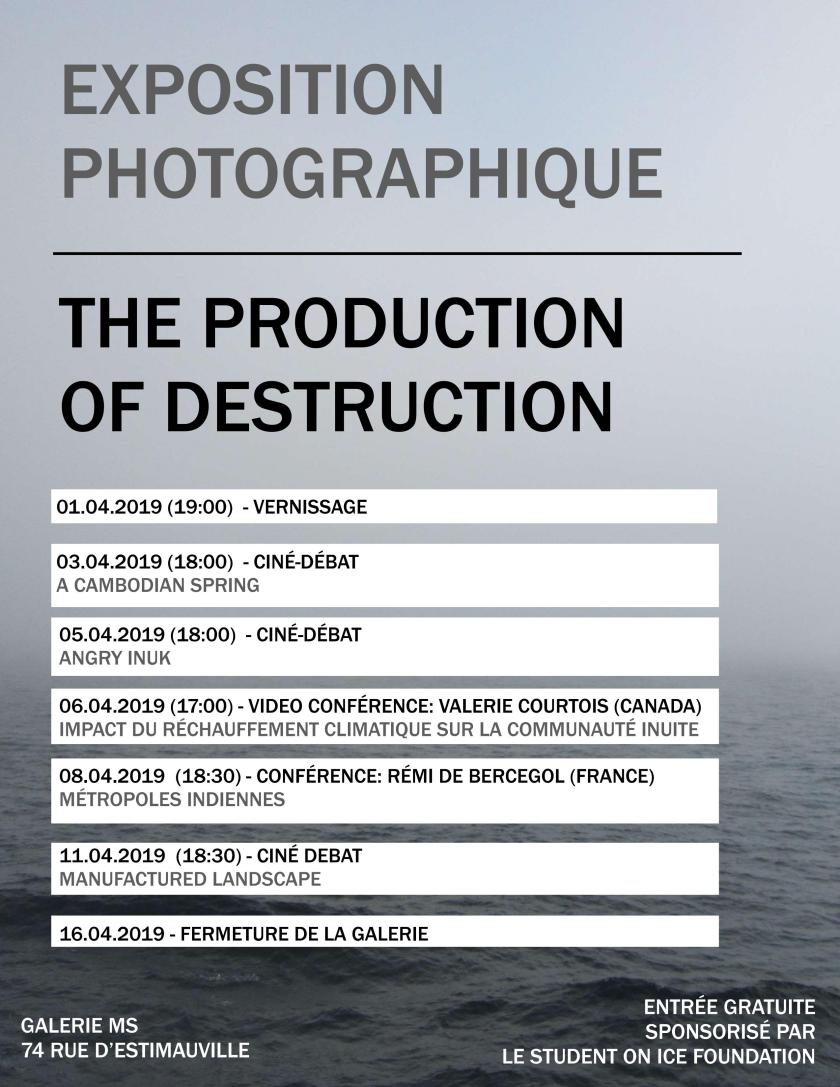

The Climate Strike in LH

On Sept. 20th, 2019, young protesters gathered on the streets in every part of the world for a better future, fulfilling the responsibility of their generation.

As part of the series of climate strikes taking place worldwide on the same day, hundreds of students in Le Havre skipped schools to join the protest, including approximately over 30 Sciences Po students.

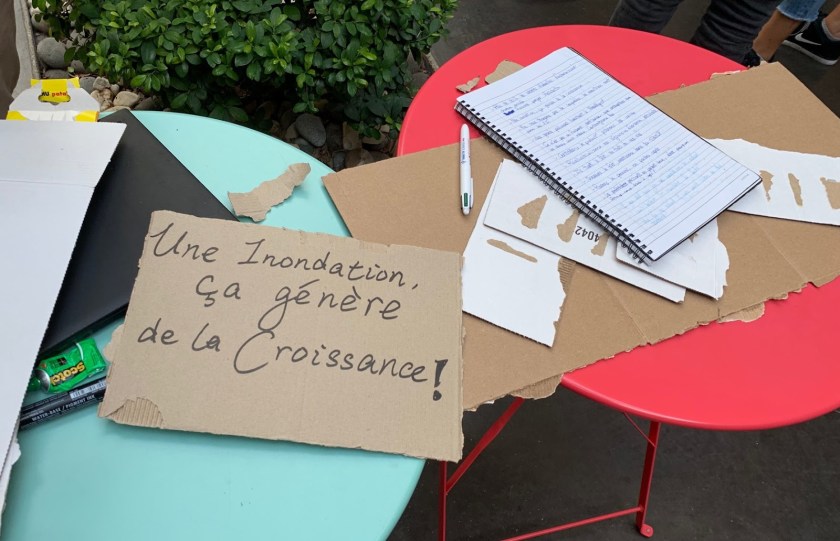

Days before the strike, Sciences Po students were informed that absences would still be counted during the strike. This did not extinguish the passion, nonetheless, of those who were firmly willing to participate. On the Le Havre campus, the preparation for the strike had started the day before, when active students met to prepare for the coming protest, writing slogans down on posters.

“A flood generates the growth!”

On Friday morning, students met in front of campus and headed to the University of Le Havre, where the strike would begin. At around 10:30 a.m., the protestors started to march through the city, with more joining the march later. A small proportion of the protestors, notably, were not students but non-student citizens of Le Havre. Some participants of the strikes were members of Mouvement Jeunes Communistes de France (JC) and several JC flags could be seen during the march. Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) also participated.

The strikers marched through the city from the University of Le Havre to La Plage, carefully avoiding possible negative impact on neighborhoods and public transportation. At approximately 12:00 p.m., the strikers arrived at La Plage, gathered at a square. After the organizers of the strike delivered a speech on the emergency of climate issue, the strike ended.

Why is there a strike?

The climate strike on Friday in Le Havre was a part of the series of international strikes and protests, a.k.a. the “Global Climate Strike” or “Earth Strike.” The full week from Sept. 20 to 27, called the “Global Week for Future,” is a worldwide week-long strike. Inspired by Skolstrejk för klimatet (School strike for climate) initiated by Swedish young activist Greta Thunberg, the participants of the worldwide strikes are predominantly students. Since August 2018, Greta started to protest in front of the Swedish parliament and skipped school every Friday.

Youths have the responsibility to act and demand changes because their previous generation has failed to treat climate change as a crisis and actively respond to it, as the slogan “If you do your job, we would be at school now!” reveals.

Greta’s action has become a global movement. The strike on Sept. 20, 2019 is the third global strike in this movement, with the previous two in March and May this year, which had smaller numbers of participants.

Although this movement is highly decentralized and grassroot, its mobilization has been a huge success. Over 4 million people around the world participated in the climate strikes on Sept. 20th. In France, it is reported that roughly 40,000 people participated, with the gilets jaunes (“yellow vests”) joining the climate protest on their 45th Saturday of action.

The UN Climate Action Summit will take place on Sept. 23, 2019, three days after the strike on Friday, in New York. [5] The strike on last Friday was timed to put pressure on the summit, demanding a realistic solution.

In Defence of the Strike

Unsurprisingly, the movement confronts criticisms from many perspectives. Some consider the young protesters truant, while some other claim that the movement is not practical. A widely supported argument opposing the strike, noticed on social media, is that the strike is not constructive since it cannot bring viable solutions and actual changes. According to this argument, these can only be achieved through the effort of scientists and policymakers, and thus the movement is a waste of time. The key issue is, therefore, in what way these strikes are able to achieve their goal.

Jürgen Habermas’s Public Sphere provides a direct approach to prove the constructiveness of the strikes: in such a discourse-based sphere, the active participation of the public is essentially a contribution to the advancement of the social agenda. Critically, the domination over discourse often aligns with the established frame and domination in policy-making, which makes breaking the bondage of disciplinary discourse a rebellion against the political establishment.

“Before most of the children who will be striking were born, scientists knew about climate change and how to respond to it,” says Kevin Anderson, a climate scientist. The scientists’ open letter in Science magazine also states that “many social, technological, and nature-based solutions” are already available. The scientific community recognizes the failure to respond to climate change a consequence of ineffective governance rather than a lack of alternative solutions.

It is not to blame politicians and governments for being blind, but it should be realized that in the legislation process, other considerations are taken prior than environmental concerns. In this manner, the popular discursive participation, through mobilizing the teenagers who are excluded from the political establishment, is fundamentally a contribution to the improvement of governance.

It doesn’t mean all the movements are constructive – only certain kinds of movements contribute discursively. Movements should not be person- or concept-oriented but agenda-oriented to challenge the domination over discourse. The significance of a popular movement opposing existing norms, like the climate one we are experiencing, is the popular participation for the purpose of advancing a certain agenda which would effectively undermine the establishment.

The political sociologist Anthony Orum also explains the indirect role of civil societies and movements in legislation; although the mobilized masses are not able to immediately propose alternatives, through linkage institutions, they are capable of advancing legislation by pressuring actual actors. In a parliamentary system, for instance, a popular movement would empower the opposition parties or MPs to find an alternative solution. Another possibility is that the ruling party or parliamentary majority would gradually embrace the movement’s demands to maintain its standing.

The case of Germany could prove the significance of public actions in the legislation process. Germany has a strong tradition of civil disobedience on environmental issues – in the Friday strikes, there were over 1.4 million protesters across Germany, comparing to the 40,000 in France. Consequently, the ruling parties have to constantly make compromises to the greens, on both national and local levels, due to the pressure from activists. The Social Democratic Party, before losing the 2005 election, even had to form a coalition with the greens (Alliance 90) to gain a parliamentary majority, which is a time witnessing a huge progress in environmental legislation. When Merkel’s grand coalition came to power in 2005, although it had a firm majority in parliament, Merkel’s cabinet had to occasionally accept environmental groups’ demands for fear of losing popularity among them, which would probably lead to a second SPD-greens coalition’s victory.

When I visited Germany in June, I saw a well-designed and -developed recycling system of cans and plastic bottles, as well as the celebrated efficient garbage classification, clearly a result of the effort of the past movements in Germany. The goal of strikes, thus, is to generate a flood that revolves the watermill of political machines, to produce a revolution of our time.

Photos by Emo Touré, Yufeng Liu, Zhenhao Li