Inspired by the Humans of New York platform, first year student Jason Trinh interviews Lucas Lam. He intends to write down the stories of our students on campus, and connect them with the bigger relevant issues in society.

You have heard of Vietnamese Americans. Their stories are everywhere, some of them best sellers like Thanh Nguyen or Ocean Vuong. But what about the Vietnamese French? Today I will tell you the story of Lucas Minh Duc Lam.

When I first arrived on the Sciences Po campus, the most commonly asked question, both by other students and by me when greeting new people, is “Where are you from?”. I answered the question easily, and admittedly I even felt a little bit proud of the answer I could offer, knowing that I was the only Vietnamese student going to the Le Havre campus this year. I was born in Vietnam to a Vietnamese family, speak Vietnamese fluently as a mother-tongue, had a Vietnamese upbringing and attended Vietnamese schools. It’s the life of an average Vietnamese. However, my I was surprised once when I answered the question with the same answer. The person went, “I think there is another Vietnamese”.

It turned out that the Vietnamese mentioned was Lucas Minh Duc Lam, but unlike me, he is not the “average Vietnamese”, or at least that was my impression when I saw and talked to him at one of the first social events. His vibe let me know immediately that there was some familiarity; he is humble, a little bit shy (maybe because we spoke in English?); he even looks like one of my cousins, who is really thin with slender hands and a short, carefree haircut. I couldn’t help but feel extremely curious: being in Vietnam for my whole life and surrounded by other typical Vietnamese, I did not really understand the life of Vietnamese abroad – those who are originally Vietnamese, but officially some other nationality. I have heard of the Vietnamese-Americans: they are easy to recognise as most of them call themselves Vietnamese, most of them migrated to the United States after the Vietnam War by highly dangerous ways such as boats, hence the birth of the term “boat people” which is often used to describe first generation Vietnamese-Americans. Some of them are very widely known authors such as Viet Thanh Nguyen and Ocean Vuong. But I have never heard of the Vietnamese French. I decided to interview Lucas directly, and this article is the recap with some reflections with the talk I had with him.

***

We had our talk in the library, one Friday afternoon right before the Fall break. I texted and asked for Lucas’ participation before, with his first response being, “I’m afraid I’m not an interesting person”, reaffirming my impression of him as a very humble one. I started the conversation with some very basic question: his childhood, his upbringing, his parents, etcetera. Lucas’ parents are of Vietnamese origins. Officially, Lucas is French. He was born and raised in France, around Paris, speaks French fluently as his mother-tongue, had a French upbringing and attended French schools. He was even named a French name, with his Vietnamese middle names rarely used. Spiritually, he is… also French. Lucas does not speak Vietnamese well; he does not identify as a Vietnamese, not because he is not proud of his origins, but rather because his parents raised him as an integrated French citizen, and now he just feels more French than Vietnamese. “It seems to me that there are two types of Vietnamese here” – Lucas told me – “The first type is the very patriotic one. My friends from secondary school, some of them have Vietnamese parents,and they were raised in France. Whenever somebody asks for their identity, they say they are Vietnamese. The second type is me.”

However, he also expressed that his parents helped him appreciate his culture and reminded him of his origin: they “only cook Vietnamese food” for him when he is home (which he admitted that he enjoys very much) and sent him to a school that had Vietnamese in his subject choices (there are only two of them in Paris). Lucas still identifies as French not Vietnamese, because other than the food and some of the basic spiritual or celebratory rituals like the Vietnamese New Year festival Tết or the famous Vietnamese food phở and bánh cuốn, he admitted that he doesn’t know much about the Vietnamese life. “My parents don’t want to erase my origin, but they wanted me to integrate into French society, to feel like a French person. After all, Vietnamese is just my origin; French is my nationality.” He also told me that among the Vietnamese community in France, it’s not always the same, but in his case, even his parents feel very French nowadays, as they have lived in France for more than thirty years. “I think it’s very nice to be allowed to be a part of French society and at the same time respect your own origin.”

I asked him more about his parents and their political opinions as the discussion moved to a more political sphere. His parents, from small provinces of Vietnam in both the North and the South, came to France as a result of the Vietnam War; but unlike most first-generation Vietnamese Americans who are highly anti-communist, his parents are said to be neutral in Vietnamese affairs. They just wanted to maximize their opportunity abroad, he said. I asked him if the community of French people whose origin is Vietnamese holds the same political position. “It depends, really. Many of them are very anti-communist, yes. But many are just like my parents who feel more French than Vietnamese, therefore they now only care about French politics.” He also admitted to me that his parents do not talk to him much about Vietnam.

He spoke of his experience as being “the only Asian in the whole school” back in the time when he lived in the countryside near Paris. He was mocked at school, but fortunately he was backed and defended by many friends. When he moved inside Paris which is a melting pot with many different people, he and even his friends never experienced racism again. He told me that there are many stereotypes – or “cliché”, to use his word – about Asian people, but most of them are good ones, such as Asian people are hard-working, intelligent and good at math. “I think the racist, bad cliché targets black and Arab people, so it’s much harder for them.”

***

At the end of the conversation, we talked about Sciences Po, about why we chose Sciences Po, about our future occupations. When asked about his plans for his future kids, if any, he told me that he would try to teach them about Vietnamese culture, about Vietnamese food, but it will be hard to teach the language.

I said goodbye to Lucas and went home to prepare for the Fall break. But the conversation with him has stayed in my head for a while, until now, whilst I’m writing it down. I have always felt like the serious conversation about the Vietnamese abroad is rarely had among the Vietnamese at home; if they do exist, they are mostly offensive jokes on the internet made by the Vietnamese at home about betraying and leaving the motherland, about refusing the identity. On the other side, the Vietnamese abroad (many times the Vietnamese Americans) talk of the Vietnamese staying as the “commies”, as uncivilized and uneducated, authoritarian-loving people. The Vietnamese at home and the Vietnamese abroad, mostly Vietnamese Americans, are even divided by the version of Vietnam they identify with. The Vietnamese at home identified with the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the red flag with a big yellow star in the middle. The Vietnamese abroad identified with the Republic of Vietnam (the old South Vietnam regime back in the Vietnam War) and the yellow flag with three yellow stripes. The division is deeper than anything non-Vietnamese people can imagine. Many people are surprised when I tell them that I could not walk into a Vietnamese-owned phở restaurant in the United States and speak Vietnamese, because then my Northern Vietnamese accent would be exposed, and Vietnamese Americans might behave badly as a response.. The understanding between the Vietnamese at home and the Vietnamese abroad is almost non-existent. That is why when President Donald Trump decided that he could deport Vietnamese migrants from the Vietnam War back to Vietnam if they have any criminal offences, it hurt the Vietnamese community abroad in an unimaginable way: the Vietnamese government wouldn’t recognize or accept those people into Vietnam, and the Vietnamese people also wouldn’t sympathize with the deported people.

Maybe because of the strict censorship in Vietnam. Maybe because of the deep, penetrated hatred inside the people abroad who fled the country out of fear. But the conversation has never occurred, and I’m just very glad that I had the chance to talk to a Vietnamese who has grown up in a Western country, from the other side of the world, the other side of the conversation. Maybe the Vietnamese community in France isn’t as hateful towards the current Vietnamese regime as the community in the States, but there are undeniable differences in our mindsets, our lifestyles, our upbringings, and our opinions.

The current event in which 39 bodies were found inside a container in the United Kingdom, most of them suspected Vietnamese nationals trying to immigrate, sparked conversation among Vietnamese people. Vietnam nowadays is not having any wars and the economy is growing very fast, but the trend of immigration is still visible because many (mostly poor) people dream about the Western life and then follow the smugglers to migrate to Western countries. Is it illegal? Yes, but one thing that rather privileged people like you and me don’t understand is the desperate feeling of having no choice, of wanting to be better and to provide better for your family.

It is important to remember that not all immigrants’ stories are warm-hearted stories. People like Lucas and his parents can be said to be very lucky, to not only successfully come to France but also to successfully integrate into society. But somewhere out there, there are immigrants who die in freezing containers at -25*C, with their desire to have a better life unfinished, and we shouldn’t forget about them.

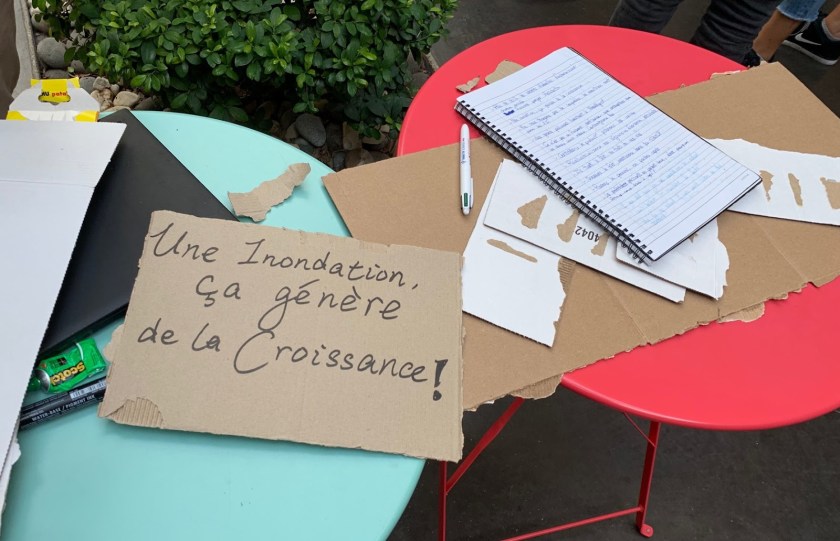

Photos: author.