by Kristýna Poláchová

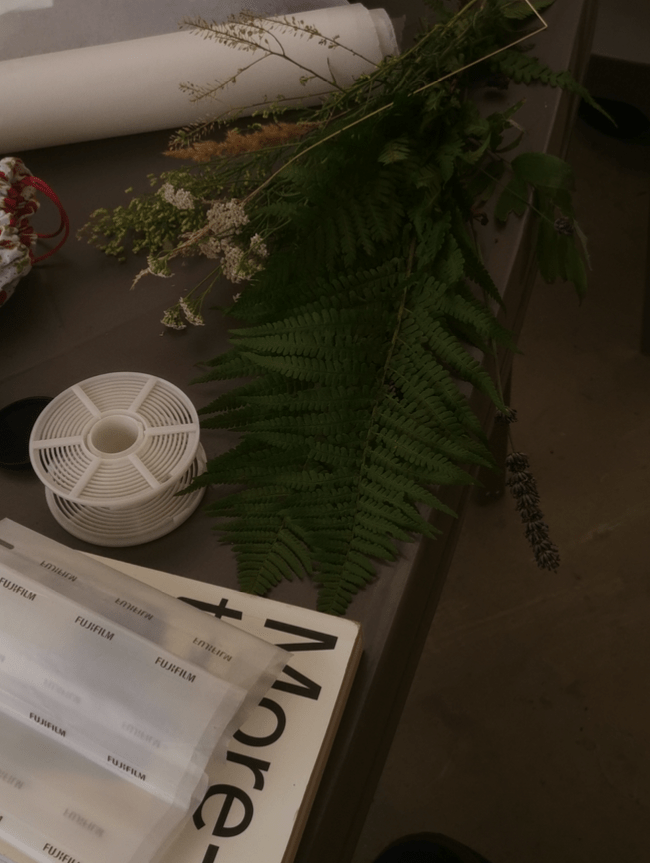

As a person interested in analogue photography but also caring for the environment, I often asked myself: can a darkroom ever be sustainable? Through these reflections, almost as if I manifested it, I had the opportunity to attend a workshop on this specific topic last summer. This article will thus be an hommage to this workshop and to all the inspiration I gained from it as well as a ‘cookbook’ which came together afterward. I am thankful to Michaela Davidová for sharing these moments of experimentation and discovery with us.

Making the whole process of photographic development sustainable is not an easy task and the inclusion of a question mark in the title of this article serves partially to encourage reflection on the process as a whole. This question is not purely material or processual but also philosophical – do we perceive photographic material simply as a means for realisation of our ideas? Isn’t the darkroom itself an organism transforming and digesting materials? Let us ponder these questions further while we proceed to a practical application of this approach exploring ‘recipes’ for DIY film developers from less toxic materials.

For black and white negative processing, one generally needs a developer, an acidic stop bath, and a fixer to transform the taken latent (invisible to the eye) image into a visible one. Commercial developers are generally based on organic compounds derived from benzene. For plant-based DIY developers, we need to use ingredients containing phenolic acids (phenolic compounds structured on a benzene ring). Those can include coffee, mint, wild thyme, or urine. Phenolic acids can be extracted from them by, for example, pouring hot water over them and letting them cool down, boiling the plants in hot water, or by cold extraction through maceration (storing in an air-tight container in a liquid made of water, oil and alcohol for 3 days). The second ingredient needed is alkali since the developing process can only occur in an environment with pH>7, and alkali helps to achieve higher contrast and more grain in the final image. The most commonly used option is water-free sodium carbonate (= washing soda). The following ingredient is ascorbic acid (vitamin C) which helps to reduce the developing time. By mixing vitamin C (pure ascorbic acid) with sodium carbonate, we get sodium ascorbate. The final ingredient needed for a DIY developer is water.

The stop bath needs to be an acidic solution in order to interrupt the alkali-developing process. As a more accessible substitute for a commercial stop bath, we can mix water and white vinegar. Lastly, to make the image permanent, we need to bathe it in a fixer. There is not a perfect substitute for a conventional fixer (hypo or ammonium thiosulfate), but it is also possible to use salt-fix, although it serves more as a stabiliser and doesn’t have such long-term archival qualities.

0,5L Caffenol-C (coffee-based ‘soup’) recipe:

Ingredients:

– 20g of water-free washing soda dissolved in 1/3 of 0,5L of water

– 5 g of vitamin C dissolved in 1/3 of 0,5L of water

– 20g of instant coffee dissolved in 1/3 of 0,5L of hot water

(source: Blog – Plant-based/DIY developers – michaela davidova)

Directions:

We start by mixing the ingredients in separate containers with water at 24°C. First, we mix the solution with soda, then the solution with vitamin C, and lastly the solution with coffee.

We let the mix develop for 12 minutes, agitating during the first minute and then 10 times each following minute.

Film roll used: Fomapan ISO 100

Remarks: Pictures have quite high contrast, however the film is slightly over-developed. It is possible that 10 minutes of development would have been sufficient.

One-week-old Caffenol-C developer:

Oregano developer

For more information, visit: