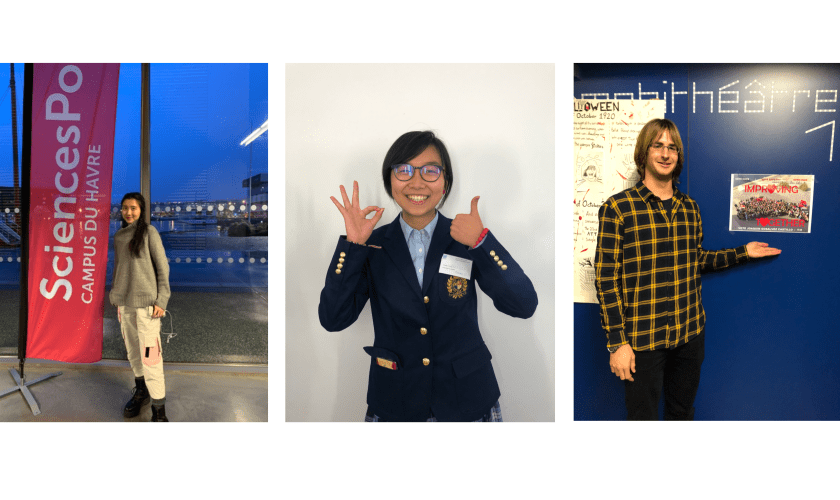

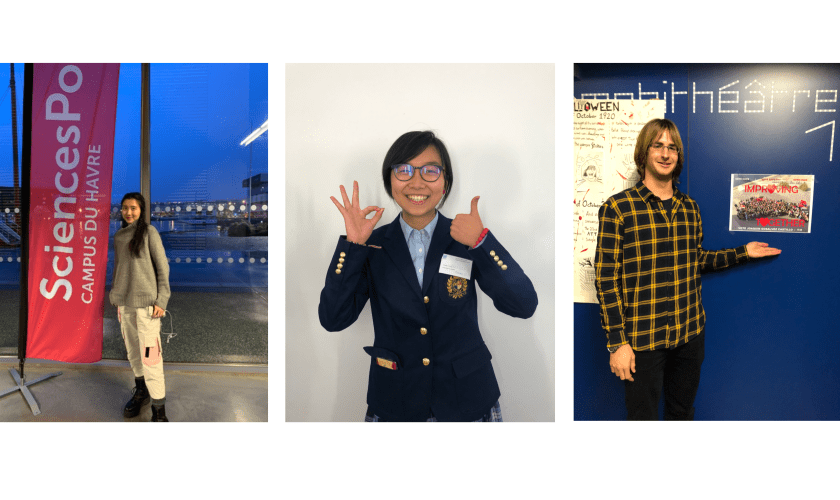

First year student Ashley interviews the three year rep candidates to find out more about them and their ideas and motivations.

Running for Year Rep is no easy task — it requires devising new ideas to improve the Sciences Po community, an inordinate amount of effort, and knowing how best to capitalise on the allure of food.

While each candidate often does their best to pitch their ideas to a range of people during the campaign period, you might not have had this one-on-one opportunity. If you’re still deciding on who to vote for as the election date approaches, the responses of this year’s candidates’ (Any Li, Joaquin Castillo and Zhenhao Li) to our questions might help with your deliberation.

1. Campaign mottos and ideas aside, tell us more about yourself. What is one thing people don’t know about you?

Any: I play several kinds of instruments, and I’ll also be joining the KPop club after Diwali. One interesting fun fact is that I dream very often and they usually come in a series of stories; I remember all of my dreams very clearly. Usually, people say that if you don’t sleep well, you will dream… But I have dreams every day and I remember them so clearly, as if they were movies or dramas. There was once when I dreamt that I got out of a Metro station that looked like Paris, and there was a war going on (I’m not projecting anything!) and we had to go down into a cave to hide. Then, I was elected as the spy of our group to talk to the people who had initiated the war to reach peace.

Joaquin: I agree that it’s important to know more about the candidates so I created a video on that, where I talked about liking basketball, athletics and sports. But maybe something else that others don’t really know about me is that I always try to work for people because I feel that it’s my duty to be with people and help improve their lives. In fact, I used to be a Year Representative in my high school. Another thing I would say is that I miss the hikes that I used to do with my family — we used to go to the mountains near my village (in Spain), and this provided special moments for me to discover nature and the environment, which I really appreciated. I also miss going to the beach, and going to the sea, for sure.

Zhenhao: One fun fact about me is that I don’t eat coriander because I don’t like the smell of it. Also, I think that sometimes, people may feel that I might speak better Chinese than English, but please don’t hesitate to talk to me in English because it helps me practice expressing myself in English. I just really like communicating with people, so I guess that’s one thing about me that I’d like to share.

2. What motivated you to run for Year Rep?

Any: The Year Rep is supposed to represent the interests of all students. This year, we have more nationalities and ethnicities than ever before, so I think it’s very important to represent the interests of everyone. Last year, I also worked in a voluntary organisation and we introduced policies and information flows between migrant children and schools, so I’m familiar with having to communicate with others.

Joaquin: I think we’re used to seeing ways of representation that we don’t like. I think it’s a necessity to create or innovate or prove that there’s another way to be more democratic, and to show that our representation not only listens to all voices, but is also efficient in the things that it does. I would like this campaign to, in a certain way, revitalise and provide new ideas — not just ideas imposed by the candidates on others, but also more collaborative, where ideas are shared horizontally by everyone. This is what I call “guarantees of improvement”. This is why I think that renewing and strengthening the democratic process and the way we’re being represented is particularly important for our generation, because we’re the ones capable of inventing democracy, change political systems and invent new ideas. That is why I would like to be the one to represent the ideas of the people and of all their voices.

Zhenhao: I’m running for Year Rep because I feel that it is a way for me to connect with other people in my year. I really appreciate everyone’s talent and I would love to talk to as many people as possible. I also talk about my motivations in a video I uploaded to my Facebook page, so you can check that out too.

3. Given Sciences Po’s diverse student body, how do you plan on being accessible to your peers?

Any: Firstly, I’ve joined many clubs, which consist of people from different backgrounds who speak different languages, and I get to interact with them. Speaking of languages, I’m currently working on French B1 and hopefully I’ll get to B2 by next year so that I’ll be better able to communicate with students who are more comfortable speaking in French. Personally, I don’t want to put too much pressure on students, so I don’t think I will be organising General Assemblies with mandatory attendance just because everyone is so busy. But what I will do is to create a Facebook page with a link to a questionnaire asking for general solutions or suggestions to campus-related issues. It’s fine if you don’t want to fill it in, but I just want to ensure that I’m always available if others have any concerns about both academic and non-academic issues.

Joaquin: I really want this campaign to be an opportunity for everyone, regardless of their background, to express their thoughts. I’ve been talking to people since the beginning of the campaign, who are sometimes “intermediaries” who speak with people from other classes and programmes. They then tell me the demands of other students. For the moment, I have more than 6 “intermediaries” who are both 1As and 2As, and I hope that there will be more in the next few days. Of course, I would love to listen to everyone personally, but I know this isn’t easy, so I need help from other people to be able to listen to more concerns than if I worked alone. Other than this, I’m also planning on holding some events in the coming days and will publish details on Facebook. I think both of these will help me reach out to more people, regardless of their background.

Zhenhao: My background is pretty diverse because I lived in Hungary and went to a French high school, despite only being able to speak English and Mandarin, and am also originally from China. It was quite complicated being an international student in that campus initially, but I was eventually able to overcome language and academic issues. Everyone was different in terms of their backgrounds and everyone was unique in that they have different feelings and points of view about issues, so I think this multicultural setting helped me better understand the international community. I’m also a polyglot (I speak Chinese, English and French, and a little bit of Japanese!) so I’m able to talk with different communities directly and understand their real concerns.

4. If you had to use a song to represent your campaign, what would it be?

Any: One of my favourite songs is “The Other Side of Paradise” by Glass Animals. I feel like Sciences Po is already a very ideal environment, but there are other areas for us to improve on. It’s kind of already an academic paradise, but there are still other things to improve on, and that’s on the OTHER side of paradise. I think what the Year Rep is supposed to do is to try to make this paradise more satisfactory to everyone.

Joaquin: I don’t know if this is a bit dark, but I think the song “Renegades” by X Ambassadors shows that while there are some people who don’t feel good in society, everyone is still united despite this. Comparing this to my campaign, I hope that our Year Rep, not just for this campaign but also in the ones that follow it, will help all of us feel part of this campus. I think a union between people is necessary. I wouldn’t want to see people suffering, and I want to work on everyone’s welfare.

Zhenhao: I would say the song “Right Here Waiting” by Richard Marx! It represents my campaign because I’ll always be there to help others with their problems, and I want them to know that I’m approachable.

5. What are some issues that you’ve identified about school life, and what are your plans to rectify them?

Any: I think the first thing would be to deal with information flows between 1As, 2As and 3As. As 1As, we don’t have an organised file of study/exam resources or previous class’ notes from 2As and 3As, and I think we could create a Drive or get access to the 2A’s drive. I also want to create a Facebook group with 1As, 2As and 3As, where we invite 3As to share their overseas experiences, as well as experiences with the Parcours civique. If we can publish some articles or videos conducted with the 3As during the Summer vacation, that would allow the 1As and 2As to have an idea of what our lives during the third year might be like. Of course, you can seek advice individually by approaching specific 3As, but you won’t be able to meet every person face to face or ask them questions individually… But with a page, information would be more accessible.

Also, I would like to start the Yearbook project as early as possible, since we started quite late last year. Another thing would be the improvement of facilities — we can install a mirror in the music room (Room A1), provide more food choices in vending machines if this is negotiable with the BDE and the administration, and also solve the problem of the broken microwave more quickly in the future. These are just some minor things in terms of facilities. Another very important thing is improving communication with Admin. It seems quite basic, but it’s something that the Year Rep must do. Sometimes, the Admin sends emails regarding the rescheduling of classes only a day before, and if we don’t check our emails, we might not see the rescheduled timings. I would like to see if these arrangements can be done in advance instead.

Joaquin: One thing I know is that the 2As have been seriously struggling with finding their place abroad in another university for their third year. I would like to help them by increasing the amount of information accessible to them — I think there’s a problem of orientation because we don’t usually have a lot of information about that, so I would definitely like to help the 2As with their third year abroad through what I would call the ‘LH Student Toolbox’, which will provide tools for everyone to express themselves and how they hope things will improve even after the campaign. The Toolbox will also provide essential information on Sciences Po life — for example, who should I email when I’m sick, and what is the information available for the third year abroad? I think it’s important to open the dialogue to the 3As who are currently abroad by inviting them back on campus or asking them to share their experiences, so that everyone is able to decide where to go for their third year. I also know that many people are struggling with CAF, which is why I would like to help the 1As with their integration here through the ‘LH Student Toolbox’.

Some other people have also told me that there aren’t enough microwaves, so one of my electoral promises is to buy more microwaves for students. Another proposition that I think is extremely necessary is to hold a General Assembly for students every two months, because this is another way for us to enforce our democracy. I would like to make all the ideas proposed during these Assemblies into a reality.

Zhenhao: Personally, I don’t have any big problems with school life. But I’ve been listening to people’s ideas and I’ve discovered that there are quite a few issues that we can try to negotiate with the administration. For instance, the absence policy is a problem for many people because some students may be sick for a very long time but they’re unable to get a justification from the doctor within the allowed period. Some people may also have psychological problems, which makes it very difficult for them to justify their absence. I think this concerns quite a few people, and that this issue should be addressed. Or, at the very least, we should make the absence policy clearer for students to understand why and when/how they should obtain their justification.

6. What is one challenge you foresee yourself facing as Year Rep, and how will you overcome it?

Any: For me, the most urgent challenge would probably be my proficiency in French, especially when dealing with the French administration… But I think I need to be more patient with this. Also, I think there’s a lack of interaction with some people who sign up for classes in French because they’re not in any of our classes and we don’t meet them a lot. Another issue would be the flow of information, but as long as we have Facebook pages and groups, I think this problem can be solved.

Joaquin: I think one challenge would be facing the worry of not getting what I want after voicing concerns to the school administration. To overcome this, we would need to find compromises with the administration to allow things to be improved. I think the administration is concerned with our welfare, and I would like to thank them for that because I know it’s not the same in all places. This is needed for us to make it possible for ideas to be implemented. For me, another way to overcome these challenges is to draw on my experience of being a class representative in high school to implement a recycling network. I’ve said that our school needs to be more ecological and that we need to recycle, and I managed to implement a system of recycling when I was in high school… I have experience implementing ideas that might seem complicated initially, but turn out to be achievable after good organisation and a huge willingness to see them through.

Zhenhao: My challenge is probably speaking in front of a big crowd because I’m not very used to this, and would prefer talking privately to people. But I think this may be an advantage as well, because talking to people privately could help me solve problems directly as a Year Rep. To overcome this, maybe I can attend more MUNs (which I’ve just done!) to practice my public speaking skills. The speech that I need to deliver on Monday is limited to 1.5 minutes, which is exactly the same amount of time for General Speakers’ List speeches during MUN! So I think I’ve definitely taken LHIMUN 2019 as an opportunity to train my public speaking skills.

Remember to cast your votes for your Year Representative on Thursday. After all, if our P.I. classes have taught us anything, it’s that voting is a right that ought to be exercised!

(For more information on each candidate’s campaign, do head to the following links: Any, Joaquin, and Zhenhao.)