By Yoann Guillot

All images credited to the author unless otherwise stated.

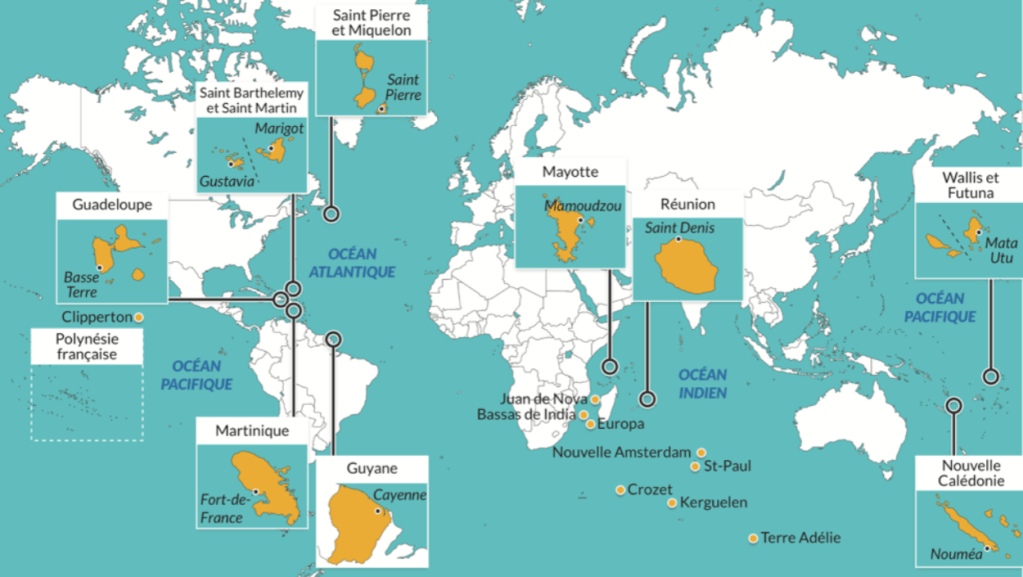

Image credit: digischool.fr

Reader, I seek not to offend, but it is well worth putting on paper that the typical view of the Outre-Mer that exists in the minds of those in the Hexagone is embarrassingly unsophisticated. Indeed, it seems as though the national imagination is chock-a-block with atrociously stereotypical misconceptions. Dear reader, I assure you, when someone only mentions “coconuts, fruits, beaches, beautiful and coloured people” (the highest degree of ignorance) when talking about the Outre-mer, many of us, quite legitimately you will agree, are irritated. Apart from “Les Cocotiers de la République” — a label coined by Canard Enchaîné to qualify (with extreme irony, and some truth) the turpitude of political and economic life in overseas territories – other descriptions are generally quite exaggerated.

Plage de Grand-Anse, Sud de La Réunion

So, nonsense aside, what really is Outre-mer, anyway?

First and foremost, it is important to expose the ideas behind the term “outre-mer”, since its definition is not that evident and should not be taken for granted. As the English term “overseas” suggests, “outre-mer” literally means what is over the sea vis-à-vis the mainland continental part of a country — the European part of France. As history and its implementation of humanistic ideas implies, “outre-mer” is intrinsically related to colonisation and slavery (you are very well encouraged to watch the film “Ni Chaînes, Ni Maitres” by Simon Moutairou, you can see it in French now at the cinema). For a long time, it remained and was employed as a synonym of “colonies” as a euphemism. Two striking examples of that were, firstly, the renaming of the “Musée des Colonies” (museum of colonies) to the “Musée de la France d’outre-mer” (museum of French overseas), and secondly, the replacement of the “ Ministère des Colonies” by the “Ministère des Outre-mer”. This sense remains attached to the term even after the creation of the Fourth Republic that juridically and officially put an end to colonisation. After the decolonisation of Africa, Outre-mer still alluded to departments are territories that are still under the control of France. This same word is used to this day. Even though it is obvious that the history of the term is no longer daily mentioned, it still bears its scars. This has justified the temptation to change the word, with no real success.

Another term deeply linked with Outre-mer is “la Métropole” (the Metropole), which is not spared by some controversies. In opposition to the far territories overseas, the Metropole refers to the “mainland,” the “main territory.” This is not neutral, as the same “mainland” was the one centralising all political, economic and cultural power at the expense of the colonies which were being exploited. Because of the very principle of colonisation, despite overseas territories’ ‘contribution,’ their inhabitants were refused equality, citizenship, and the fruits of true development. This term evidently still has an unequal connotation. That is why the French government has quite recently promoted the term “L’Hexagone” in replacement, with limited results. Why is this word less problematic? Because it suggests that the Hexagone is only the hexagonal part of France among others. France is thus not anymore conceived as a European mainland with anecdotal small and remote islands elsewhere, but an aggregation of continental parts and islands around the world. Yeah! Everyone lives in peace and harmony! Of course, this beautiful discourse, which puts stars in our eyes, is completely idealistic and only theoretical (oops!). We can observe that overseas territories are far from being at the core of the country’s agenda, nor are they oft-mentioned in the hexagonal news, if at least positively and not in an exaggerated manner. What you will most often hear about is the occasional cyclone in La Réunion, hurricanes in Martinique and Guadeloupe, immigration in Mayotte, and chaos in New Caledonia-Kanaky.

This new language and these new names for far-off parts of the country are definitely not erasing the latent inequalities between the Hexagone and overseas territories. The reality of most of these territories includes late development, socio-economic difficulties borne by many, and uncontrolled inflation, most of which are an inheritance from France’s colonial legacy. Some recent improvements have materialised, and this must be acknowledged as well.

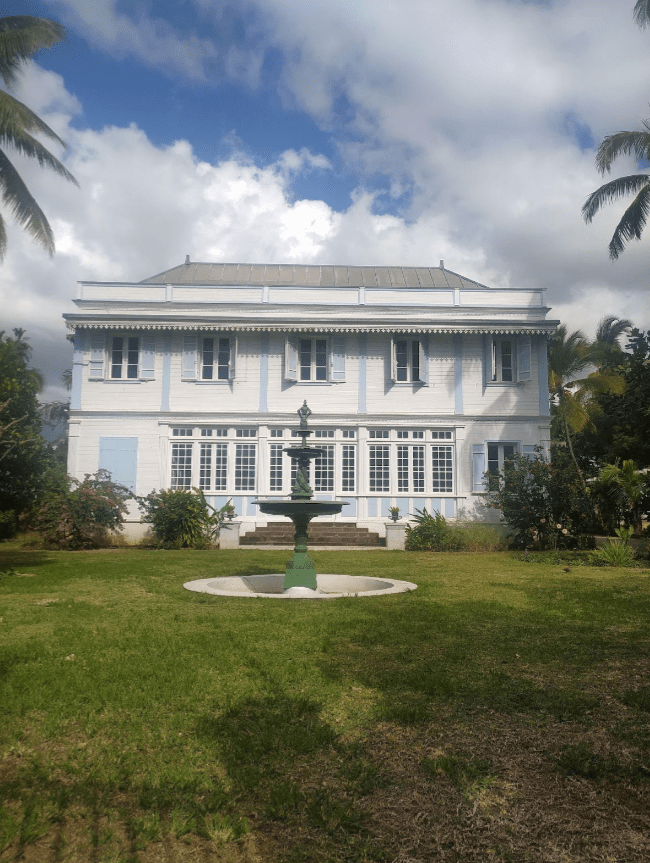

Case créole Saint-Denis-de-La-Réunion

So, is it the end of the story? Do we finally know what the Outre-mer is at this point? No! In fact, “Outre-mer” is very lacunar in describing the immense diversity of the territories it is supposed to name. First, the Outre-mer does not have a statutory unity, it is a real mess! For the record, La Réunion and Guadeloupe are a “department and region of Outre-mer”; Mayotte is a “department of Outre-mer”; Guyane and Martinique are “unique territorial collectivities”; Saint-Martin, Saint-Barthélemy, French Polynesia, Wallis-and-Futuna, and Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon are “collectivities of Outre-mer”; and finally, New Caledonia-Kanaky is a “sui generis collectivity”. “What on earth is that!?” you may exclaim, gracious reader — and with good reason.

To prevent this article from being too boring, I shall only explain that nearly each territory has its own special attributes from limited autonomy, as any other region or department in the Hexagone (La Réunion, Mayotte, Guadeloupe), to a higher degree of autonomy (New Caledonia-Kanaky). These different statuses are actually a result of each territory’s history, and this fact has multiple implications concerning the governance of these territories. For example, without providing too many details, a distinction can be made between the territories that were part of the first colonial empire (From the 17th century) and those of the second colonial empire (from the 19th century). Reunion Island, for instance, belongs to the first case, whereas New Caledonia-Kanaky and French Polynesia belong to the second case. This justifies in part why Reunion Island did not ask for further autonomy, thinking of itself as a constitutive part of France, whilst Polynesia and New Caledonia, for example, are claiming a differentiated identity. Also, to a very limited and approximative extent, we can make a further distinction between territories that were empty before the arrival of France (like La Réunion) and those that were already populated (French Polynesia, New Caledonia-Kanaky and Wallis-and-Futuna). However this rule does not apply to Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte and others who, despite the presence of indigenous peoples before colonisation, do not enjoy a developed autonomy. This is explained, in the two first cases, by the fact that these tribes were massacred with few survivors.

For sure, diving into the history explaining overseas territories current realities is neither a funny nor easy endeavour. And yet, we assert with strength that knowing our roots is the way to move forward.

To give a more positive voice, however, we can let you know that, in spite of the demons of history, overseas territories are striving to turn a new page and write a brighter future. This is the ideal we should all embrace with vigour.

Lagon de l’Hermitage-les-Bains, La Réunion

During this year, the writer of these lines will do his best to present the Outre-mer as completely as possible, to deal sometimes with its hard realities, but also with its limitless diversity and magnificence in all aspects. I invite you to join me on this journey!

As a final word, I find it very valuable to leave the floor to the intellect of Paul Vergès, one of the greatest and most widely recognised artists of Reunion Island, concerning his aspiration for a humanity of solidarity: “C’est cela la Révolution aujourd’hui. Et ce rêve n’est pas l’utopie dans laquelle on s’isole de la réalité. Au contraire, ce rêve nous permet d’aller constamment à l’idéal et d’exiger en même temps de comprendre le réel. Ainsi, ce va-et-vient permanent permettra que l’un soit lié à l’autre, que l’un dépasse constamment l’autre et fasse de chacun de nous un être responsable.” Reader, I hope you have been enticed to pay special attention to this column in issues to come.

Yours &c.,

Yoann