By Beau Sansoni

All images credited to the author.

Burmese history is long and storied, but is generally quite overshadowed by its modern politics. The people of these lands find themselves in one of the world’s most oppressive dictatorships, or under one of the many rebel militaries, with each fighting one another for dominance of either their region or the whole country. The war, however, should not discourage learning and intrigue into the past of Burma. Prior to the modern wars , military juntas, and British colonisation, there were a myriad of kingdoms and peoples that inhabited these valleys. This article will be a history of the Burmese Kingdom of Bagan from my own knowledge, and using photographs I took during my recent trip to the country. Should you wish to know more about broader Burmese history, I highly recommend Thant Myint-U’s books on the subject, particularly The River of Lost Footsteps. Another option is the Youtube channel Fall of Civilizations, and their episode on Bagan, which is more digestible at 2 hours in length.

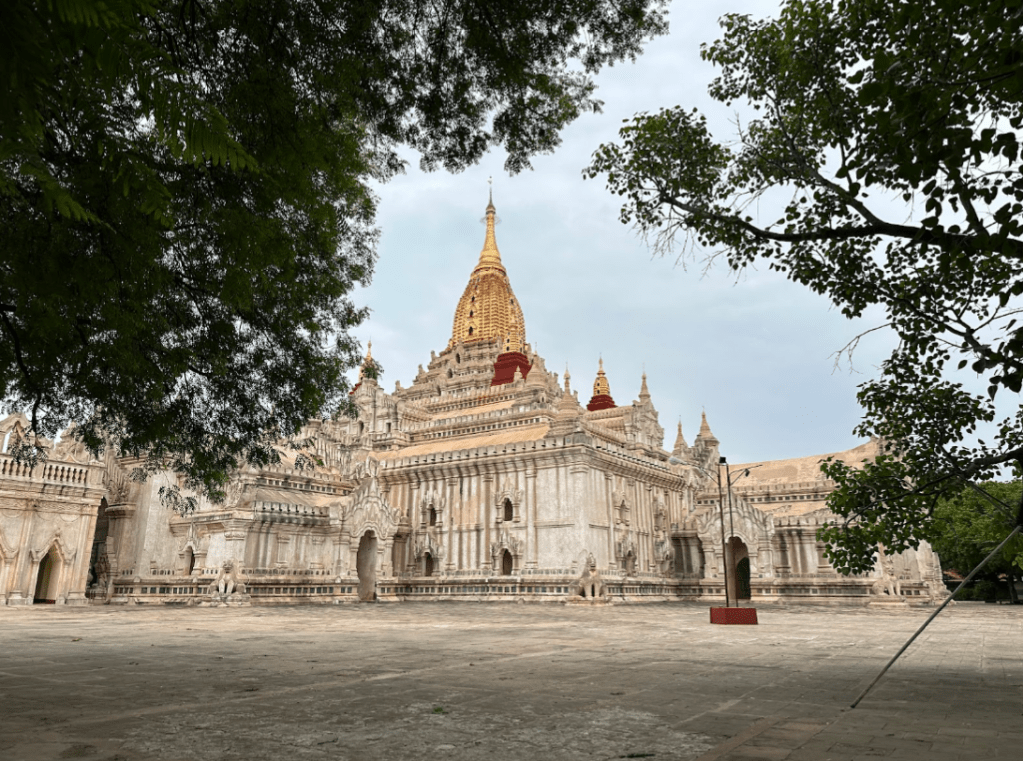

↑ Above: The Ananda Temple, photographed from the South-East.

To begin, the Irrawaddy river valley, the core of Burmese society as we perceive it today, was initially inhabited by a range of culturally similar, brick walled city states. Taking root during the period of Late Antiquity, they were dominated by the Pyu peoples, who adapted their Sino-Tibetan language to a Brahmic script, and adopted various forms of Buddhism and Hinduism.

However, at the beginning of the Western Mediaeval period, the Pyu City States had found themselves in decline. War with the Kingdom of Nanzhao brought alongside them the first Burmese, who migrated into the Irrawaddy river valley. Here, a short ways downstream from the confluence of the Chindwin and upper Irrawaddy, perhaps on the ruins of an old Pyu city, they founded the city of Bagan.

The city would, for a time, be among the many Pyu cities of the region, with its focus on Buddhist architecture in a style reminiscent of the Pyu (For examples, see: Bupaya, and Ngakywenadaung Pagoda). As Bagan began rapidly expanding, and enveloping its neighbouring states, the styles in architecture, along with the society of Bagan as a whole, would change dramatically in the 11th century. The most important of these annexations was the semi-legendary war with the Mon Kingdom of Thaton, a kingdom to the south which relied heavily on trade. Burmese legends attesting to the conquest of Thaton are of various sources, many of which are more modern, such as the Glass Palace Chronicles of the 18th century. The traditional story goes that King Anawrahta of Bagan demanded that Thaton hand over their Buddhist texts in order for King Anawrahta to convert Bagan from Ari Buddhism, to Theravada Buddhism. Thaton refused, and Anawrahta mustered an army and conquered the southern emporium. What remains certain is that Bagan expanded far into the south, with Bagan-style inscriptions found farther south than Thaton.

Starting with King Anawrahta, the royal lineage would spawn a series of Temple Building kings, which would span from the 11th to 13th centuries. Anawrahta’s successor; Kyansittha, would build the first, and most popular of the great temples of Bagan: the Ananda Temple (See top image above). This temple would continue its position as one of the most revered temples in Burma, and would receive continual upkeep by future Burmese dynasties. Its style, along with the Burmese court of the era, was inspired by Mon styles which were imported along with the artisans who initially created it. It was only until King Alaungsithu, Kyansittha’s grandson, that a Burmese style would emerge, and its language supersede Pyu and Mon in usage.

As history unfolded, the empire continued its growth, attracting more merchants and workers to continue in the construction of further temples. The average resident, in their effort at piety, would commission workers and artisans, who would build a temple (or multiple) of brick and cover it with a layer of render, possibly with objects of religious significance, like votive tablets. They would also purchase slaves for the upkeep of the property, ensuring that they would have their religious efforts remain even as they departed for the next life. It would be these numerous temples, numbering into their thousands, if not tens of thousands at the empire’s height, which would be its slow demise. Many have analysed that the land usage of the core around Bagan left little for farmlands, housing, or workplaces, instead replaced by lands which produced no tangible value (in their lifetime, prior to death, at least) and were not taxable as it was managed by the Buddhist clergy. This lack of taxable lands meant that the royal administration found it difficult to raise money, and led to the empire slowly impoverishing itself. The temples which originally led to the growth of the empire through attracting artisans and traders, were also slowly killing it.

↑ Above: The Htilominlo Temple, the Upali Thein and various stupa; both ancient and modern. Photographed from the North-West of the Htilominlo Temple.

This effect came to effect firstly under King Htilominlo, in the early 13th century, who would be the last of the great temple builder kings. His work, the Htilominlo Temple (pictured above), would continue its legacy for many years to come, as it has legendary significance as it was raised to commemorate where Htilominlo would be chosen to succeed his father. The way he was chosen (via a tilting umbrella, which would point to the successor) would reflect to the temple its name, which can be interpreted as ‘the umbrella (hti) chooses the king (min)’. It would also be the site that General Min Aung Hlaing would raise a new Hti (the decorative top on many Burmese temples) prior to the coup he led in 2021, a potential gesture of piety in his efforts to become the ruler of the country.

The empire of Bagan would receive the final nail to its coffin in the 1270s-80s, being invaded by the Mongols under the Yuan dynasty. As attested by Marco Polo, the Mongols would rout the Burmese military, led by the King Narathihapate and reinforced by elephants. The Great Khan would annex the entirety of Burmese territory (although in effect only controlled the north), and would establish the son of the King of Bagan to act as a puppet ruler within Bagan. Atypically, Marco Polo attests that the Great Khan did not sack the city of Bagan (called by Polo as “Mien”) due to the sheer number of temples which were raised for kings of old, as the Mongols found it a sin to (the) “removal of any article appertaining to the dead”. A state under the previous senior generals of Bagan’s army would eventually remove the Mongols from Burma, but by then the damage had been done, and Bagan would not rise as the capital of a new Burmese kingdom. Instead the lineage of the Kings of Bagan and the generals would go on to found multiple small states in the wake of the fallen empire, reentering the south-east Asian political theatre with their newly independent neighbours, from the borderlands to the core.